The secret super powers of poop

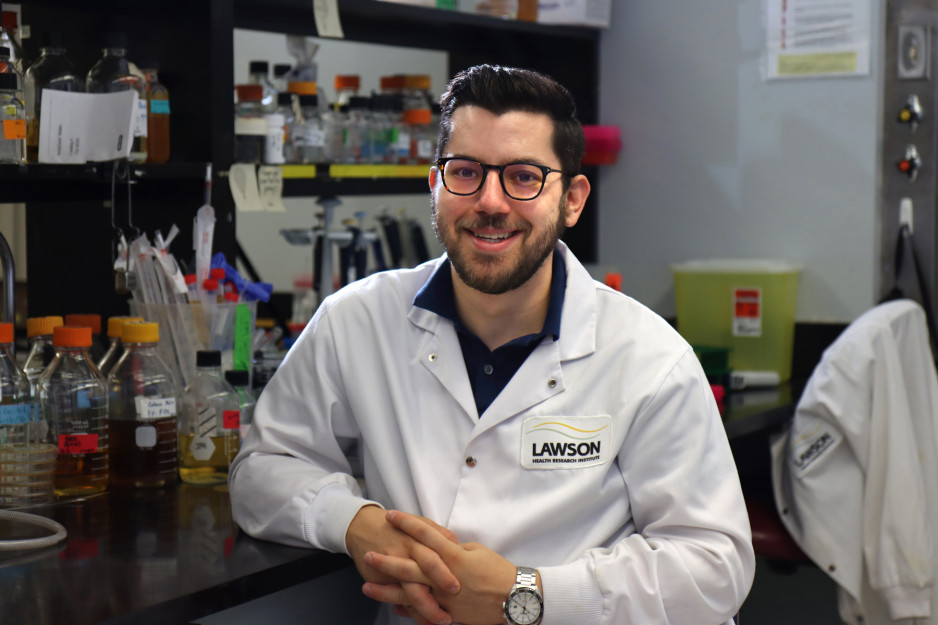

It’s quite the conversation starter. At parties or gatherings, when someone asks John Chmiel what he does, he gets a kick out of telling them “I sell poop for money.”

It’s true. He does. His own poop.

John is a poop donor.

Instead of slowly backing away, people are intrigued, says John. They want to know why and how. They quickly discover it has nothing to do with the money and everything to do with saving lives.

At St. Joseph’s Health Care London, fecal microbiota transplants are now routine treatment for debilitating and life-threatening Clostridioides difficile (C. difficile) – the major cause of antibiotic-associated diarrhea. The treatment makes it possible for people to recover from this destructive infection and holds tremendous potential in the care of various other serious diseases.

John is fascinated by this exciting new frontier in medicine and is invested – both as a donor and as a microbiology and immunology graduate student in Lawson Health Research Institute’s Canadian Centre for Human Microbiome and Probiotics at St. Joseph’s Hospital. “As a grad student, when I heard how effective fecal transplants are for C. difficile and how many trials are going on related directly to patient care for various illnesses, I thought I had to help out,” says John, who became a donor in 2018.

For many patients struggling with C. difficile, fecal microbiota transplants are critical, explains Dr. Michael Silverman, Medical Director of St. Joseph’s Infectious Diseases Care Program who has been performing the procedure since 2003 and was one of the first in North America to do so. He and his team have played a key role in the treatment, becoming the standard of best practice for C. difficile across Canada and the USA.

Most cases of C. difficile occur in individuals who are taking antibiotics and some acquire it while hospitalized. Antibiotics can destroy the normal bacteria found in the gut, causing C. difficile bacteria to overgrow. When this occurs, the C. difficile bacteria produce toxins, which can damage the bowel and cause diarrhea and other severe complications. Treating C. difficile with antibiotics kills even more of the helpful normal gut bacteria, and when antibiotic treatment stops the C. difficile returns. This can happen over and over again, making relapsing C. difficile a significant challenge to treat.

At St. Joseph’s, however, C. difficile patients are being cured thanks to poop donors like John. The success rate of fecal microbiota transplants performed by the Infectious Diseases Care Program is a staggering 96 per cent. The program is one of few performing the procedure as part of routine care for C. difficile, and the only program in Ontario – one of two in Canada - administering the treatment via capsules.

“Many patients we treat have been ill with multiple episodes of diarrhea or chronic unremitting diarrhea for many months to years, with multiple hospitalizations,” explains Dr. Silverman. “Many have lost weight and become malnourished and frail. They often are fearful that they could die and indeed, 15 per cent of hospitalized patients with C. difficile do succumb to the illness.”

Patients are “delighted” when they see a dramatic improvement after one dose of capsules, adds Dr. Silverman. “For many patients there is really no other alternative except lifelong antibiotics.”

Katharine Gorjup, 62, is among those delighted patients. In October 2021, a dental infection requiring intravenous antibiotics triggered C. difficile so severe her weight dropped to 90 pounds. At 5’ 8”, she became skeletal and unable to care for herself.

“I looked like I was dying and that’s how I felt. I couldn’t cope. It was never-ending. I begged to get care. I thought I might poop myself to death,” said the Etobicoke woman, whose bathroom humour is intact despite her ordeal.

Katharine ended up on antibiotics that had to be continually increased, caused various side effects, and was costing $300 a month even with drug coverage. The diarrhea would make a raging return with every attempt to reduce the medication. After six months with crippling C. difficile and little hope, Katharine came to St. Joseph’s, the only centre in Ontario offering the procedure during the height of the pandemic.

It took one treatment.

“Within three days, I started to feel better. My life is now back on track. I had a normal poop today – I’m so stoked! I’m good every day. Hallelujah!

Such life-changing stories are common for C. difficile patients who undergo fecal transplants, yet others are left suffering. There is a serious shortage of donors. Criteria requiring only very healthy, local donors, the ‘ick factor’ often associated with donating poop, and the pandemic has created a poop supply crisis.

“Our need for London donors is great,” says Dr. Silverman. “COVID-19 has made the maintenance of donors in the program extremely difficult. When a donor gets COVID they cannot safely donate for a period of time. Donations also have to be put on hold after donors travel to tropical countries where bowel infections are common, until we can retest their stool and assure it is safe to donate again.”

At times, there have been no eligible donors and the team has had to stop treating vulnerable patients, says Dr. Silverman.

John usually donates a few times a month and more often when clinical trials are underway. While he is currently on hold due to a recent bout of COVID-19, John says the donation process is easy and people need to get past the optics.

“It’s mind boggling for most people but the more donors we have, the more we can do. We need donors to fuel this exciting and expanding area of research, and to save lives.”

The future of fecal microbiota transplants

There is still much to learn about the human microbiome and its role in fighting disease, but ongoing studies at Lawson Research Institute, including a focus on fecal microbial transplants (FMT), are making strides in harnessing this complex system. The tremendous potential of FMT is being studied in connection with conditions as varied as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, rheumatoid arthritis, atherosclerosis, HIV, cancer and multiple sclerosis.

Be sure to read about Lawson's leading-edge work to image the microbiome and uncover a connection between the microbiome and kidney stones, and why Lawson's poop pills are making waves in cancer research, including the promise they provide for those with advanced melanoma.

The scoop on fecal transplants

What is fecal microbiota transplantation?

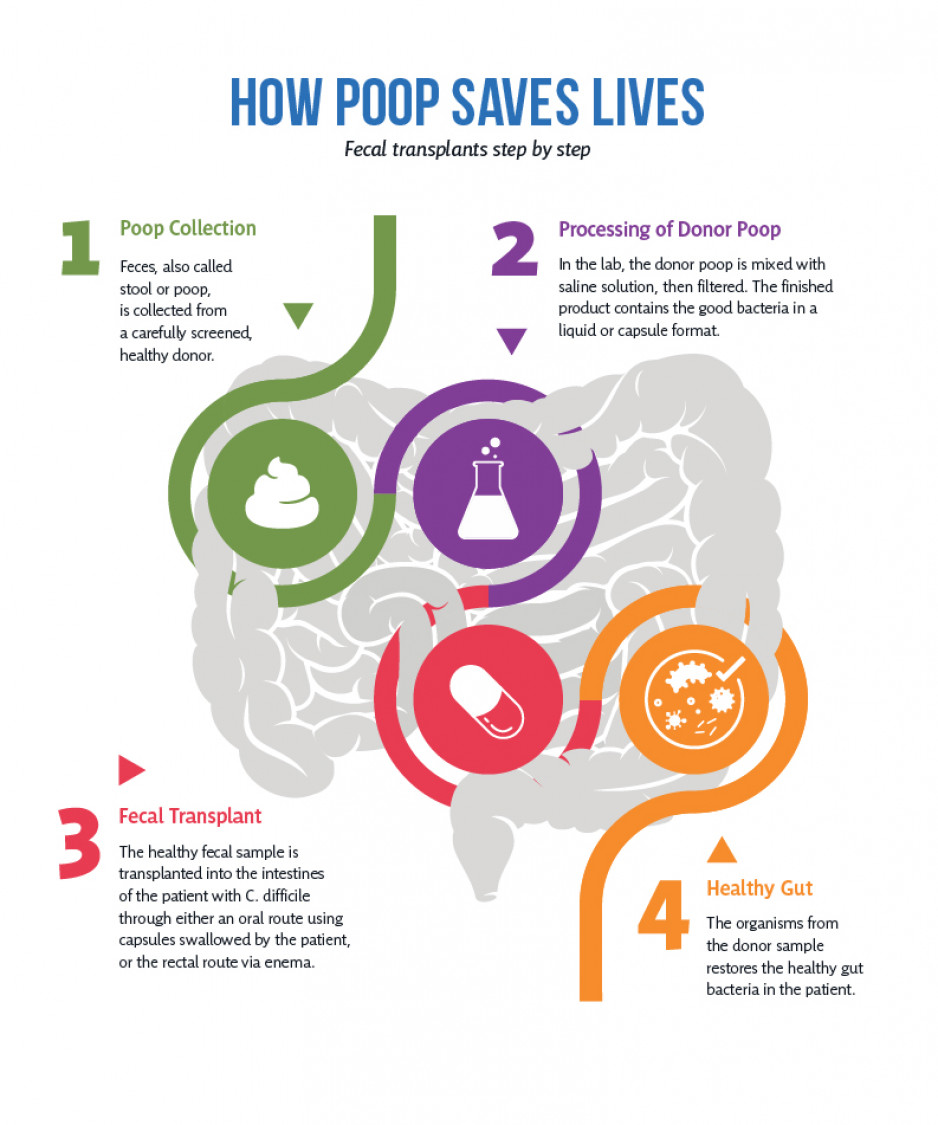

Fecal microbiota transplantation involves collecting feces, also called stool or poop, from a carefully screened, healthy donor. In the lab, it is mixed it with saline solution, then filtered. The finished product contains the good bacteria in a liquid or capsule format, which is then introduced into a patient’s gastrointestinal tract.

Why are fecal microbiota transplants performed for C. difficile?

The goal of fecal microbiota transplants is to transplant the donor’s microbiome so that healthy bacteria will colonize in the patient’s gut. A healthy digestive tract has thousands of different types of bacteria. In most cases, these bacteria are helpful for digestion, or are harmless. However, treatment with antibiotics, which may be required for certain conditions, can kill off many of the good bacteria in the colon. This can allow the bad bacteria, called Clostridioides difficile (C. difficile) to take over. A fecal microbiota transplant supplies the healthy bacteria that suppress the C. difficile, thus controlling the infection and keeping it from coming back.

What’s the fecal microbiota transplant process for patients?

Eligible patients have been treated several times for C. difficile, may have been hospitalized for the infection, and are on an antibiotic, Vancomycin, for a prolonged period to prevent relapse.

- Fecal microbiota transplants are most commonly performed through a series of rectal enemas or via a colonoscopy performed under sedation with the solution containing the donor poop delivered via a tube into the colon. At St. Joseph’s, however, the team has perfected the delivery of fecal microbiota transplantation by way of capsules that the patient swallows. St. Joseph’s is the only centre in Ontario using this much simpler and patient-friendly process. Capsules are opaque and there is no smell.

- Patients need only one treatment, which involves taking 30 to 40 capsules over 45 minutes. The patient is observed in the clinic for 30 minutes and then goes home.

It's in you to become a poop donor

Screening: To become the perfect poop donor requires an extensive screening process. Donors must be in excellent health, live a healthy lifestyle, and be between the ages of 18 and 50. A thorough review of the donor’s health and medical history will be done, including, stool, urine and blood testing. Donors should also reside in London.

Suitable donors are healthy adults who:

- have not taken antibiotics in the past six months

- are not immunocompromised

- do not have chronic gastrointestinal disorders, such as inflammatory bowel disease

If you pass the screening: Donors can give as often as they poop. Repeat screening is required every six months and a brief screening is done at each stool drop off.

Collection: A special container is provided to donors by St. Joseph’s to collect their poop. There are various ways to make collection easy and the donor can choose what works best for them.

Drop off: Donors bring their stools to St. Joseph’s Hospital. Most people poop in the morning and so they bring it fresh that morning. If they defecate in the evening, the poop can be kept in a refrigerator overnight (not more than 12 hours) and brought in in the morning. Upon drop off, donors have a nasal swab done to test for COVID-19.

Compensation: Eligible donors whose samples are used for research will be compensated for time and travel.

For more about eligibility and how to donate:

Call: 519 646-6100, ext. 65739

Email: @email

-

Are you willing to scoop your poop?

Just like blood transfusions, fecal transplants save lives. Currently there is a critical need for London poop donors. One stool void can transplant three to four people. And donors can give as often as they poop. Donors must be between the ages of 18 to 50 and reside in the London area. To find out more about eligibility and how to donate, call the 519 646-6100, ext. 65739 or email Liesl.DeSilva@sjhc.london.on.ca.

Become a poop donor today