Search

Search

Team players: FMT and microbiome research could have widespread impact

There is still much to learn about the human microbiome and its role in fighting disease, but ongoing studies at Lawson Health Research Institute, including a focus on fecal microbial transplants (FMT), are making strides in harnessing this complex system.

FMT is being studied in connection with conditions as varied as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, rheumatoid arthritis, atherosclerosis, HIV, cancer and multiple sclerosis.

FMT is already in clinical use for the treatment of C. diff (Clostridium difficile), and in addition to showing promise in the treatment of other diseases, it is also being studied as a way to improve response to existing cancer treatments and ease treatment side effects.

Dr. Saman Maleki, a Scientist at Lawson Health Research Institute and the London Regional Cancer Program (LRCP) at London Health Sciences Centre (LHSC), says they’ve just begun to explore the possibilities.

"We are just starting to study FMT as an intervention outside its traditional use in patients with C. difficile infection, and we will be expanding to other areas, particularly in cancer.”

FMT can overhaul a patient’s microbiome, Dr. Maleki explains, and a healthy microbiome is beneficial especially when a treatment is trying to activate the body’s immune system.

Dr. Michael Silverman, Lawson Associate Scientist and Medical Director of St. Joseph’s Health Care London’s Infectious Diseases Care Program, is a pioneer in the field of FMT. He has been performing the procedure since 2003 with C. difficile patients and was one of the first in North America to do so. He sees a wide range of possible applications.

“FMT has enormous potential in being an important adjunctive therapy in many cancers. It may, for example, help cancer patients respond to immunotherapy,” says Dr. Silverman, who is also Chair/Chief of Infectious Disease at St. Joseph’s Health Care London, LHSC and Western University. “The potential to impact autoimmune and metabolic diseases is also quite exciting, but still in early development.”

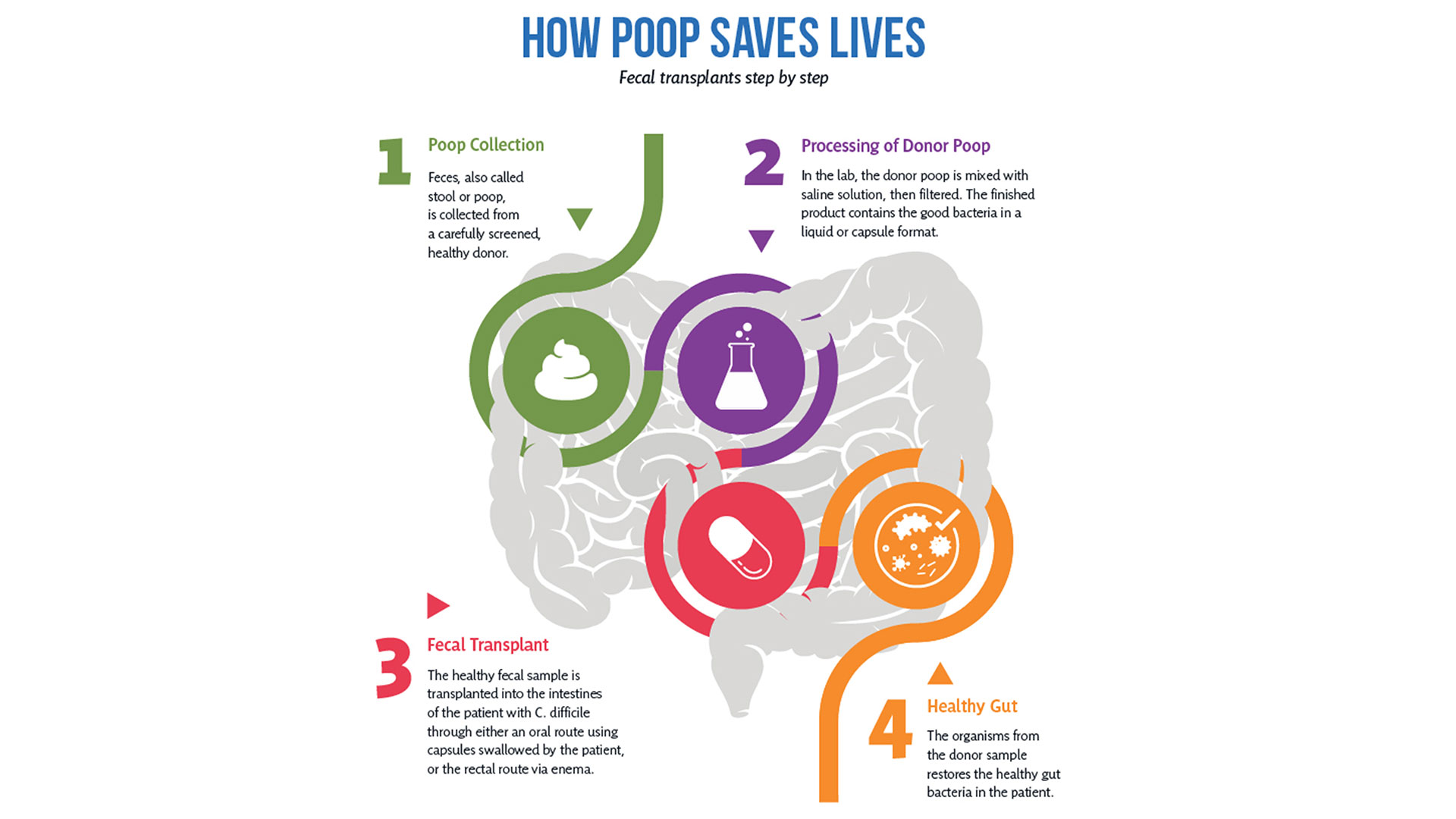

So how does it work?

After rigorous screening, stool from a healthy donor is collected and then processed in a lab into a liquid or capsule containing the good bacteria, which can then be administered to a patient’s gastrointestinal tract.

The Lawson team is also one of few delivering FMT using specially-prepared oral capsules. Introduced in 2018, they have been a game changer in patient acceptance and ease of administration, according to Research Coordinator Dr. SeemaNair Parvathy, who has been coordinating the program since 2015.

“There is a link between the fitness of the intestinal microbiome and the fitness of the immune system,” says Dr. John Lenehan, Associate Scientist at Lawson and Medical Oncologist at LHSC. “A ‘healthy’ microbiome leads to a more robust immune response when using immunotherapy. FMT from a healthy donor is expected to improve the fitness of the recipient’s intestinal microbiome and promote a better immune response.”

People with chronic disease can often experience what’s called a ‘leaky gut,’ allowing food, bacterial and microbial components to pass through the intestinal wall, negatively impacting the immune system.

“When people get FMTs their intestinal permeability improves – meaning it actually reduces,” says Dr. Jeremy Burton, Lawson Scientist and Research Chair of Human Microbiome and Probiotics at Lawson and St. Joseph’s. “What changes that intestinal permeability? The microbes at the site. They play a role in interacting with the host cells, providing nutrients and vitamins.”

With the immune system so closely tied to the health of the microbiome, it’s not surprising scientists are exploring how strengthening one can have a big impact on the other.

Boosting immunotherapy

Immunotherapy can be used to either stimulate or suppress the immune system to help the body fight disease, and FMT is showing promise in reducing resistance to the treatment.

While immunotherapy has been effective in treating a number of cancers – the number one cause of death in Canada – not all patients respond to the treatment.

But early work presented at a conference by the Lawson team for the Journal for ImmunoTherapy of Cancer has shown that using FMT to modify the microbiome could reduce resistance to immunotherapy. The study involved patients from LHSC with advanced melanoma, a type of skin cancer.

While in the very early stages, the combination of FMT and anti-PD1 immunotherapy has been found to be safe, and it appears that FMT could make tumours more responsive to the immunotherapy treatment.

“Microbiome-based treatment strategies, including FMT, have a high potential in oncology,” says Dr. Maleki. “Our team is also exploring its potential in treating pancreatic cancer.”

The research is so interesting that a recent Nature article listed the Phase I melanoma trial as “seminal” research. The study was also unique in that it used healthy donors, as opposed to donors who had previously responded to immunotherapy treatment.

A separate Lawson study with LHSC patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma, a type of kidney cancer, published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology, also looked at combining immunotherapy and FMT to ease the adverse effects of the treatment.

The Phase I study, led by Dr. Maleki and Dr. Ricardo Fernandes, Medical Oncologist at LHSC, found adding FMT to doublet immunotherapy was safe, but further study is needed to determine whether it could bring about changes in the microbiome and immune system.

Dr. Lenehan says Lawson researchers are in a position to be leaders in this field in the near future for two reasons.

“One is that other academic researchers have not been able to assemble the expertise, and some who have, do not have the access to healthy donor stool. The second is that some biotechnology companies are interested in FMT, but almost exclusively for C. difficile infections.”

Autoimmune, metabolic and other illnesses

Two other areas that have seen recent advances include FMT for the treatment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and multiple sclerosis.

“The gut microbiome is very important in the metabolism of foods and metabolic products. It can therefore have a major effect on obesity and atherosclerosis,” says Dr. Silverman. “It also is tightly involved in regulating the immune system and therefore moderating the microbiome may potentially impact autoimmune diseases.”

A study published in 2020 by the team in The American Journal of Gastroenterology showed that FMT appears to reduce intestinal permeability in patients with NAFLD.

The number of people with NAFLD is growing rapidly and studies show patients have different microbiota than healthy persons.

The trial included 21 NAFLD patients from LHSC and St. Joseph’s. While the researchers found no changes in percentage of liver fat or insulin resistance, they observed significant reduction in intestinal permeability in those patients who had elevated intestinal permeability at the study’s start (seven patients in total). They also observed changes to the gut microbiome in all patients who received a fecal transplant from a healthy donor.

“Metabolic syndromes including obesity and its complications of NAFLD and atherosclerosis are massive public health problems. Any impact on these would be of huge importance,” Dr. Silverman adds. “Autoimmune diseases also cause major morbidity and mortality. We have a lot of work to do before we can consider FMT as a routine therapy for any of these conditions, but the long-term promise is great.”

Research into the use of FMT for treatment of patients with multiple sclerosis is in the very early stages. But patients with MS show a difference in gut microbiota and higher small intestine permeability, which could contribute to the development of the disease.

A Phase I trial by the Lawson team published in the Multiple Sclerosis Journal – Experimental, Translational and Clinical, found FMT to be safe and tolerable.

While the study was very small, MS patients treated with FMT were found to have beneficial changes to gut microbiota and intestinal permeability, but further study is needed to determine if FMT could be used as a treatment.

Lawson scientists are also currently studying the use of FMT for patients with atherosclerosis, along with ongoing studies on melanoma and lung cancer. Funding for a study on pancreatic cancer has been secured and researchers are in the process of planning trials for a number of other applications.

Dr. Lenehan says, “The microbiome is connected to several diseases and their treatments. Evidence is growing that an individual’s health is related to their microbiome.”

The donor challenge

The challenge of finding fecal donors for FMT and the cost of that process remain an issue for research into this promising treatment, even as more potential applications are discovered.

There is currently no process in place to match donors and recipients – as with organ donation – but there is an extensive screening process for both infectious and non-infectious conditions, one that needs to be repeated if a donor experiences any lifestyle changes.

Dr. Burton says, “We still don't understand the full role of the microbiota. We have to ensure that we're not giving patients a microbiota that might cause them some other issue in the future, so the donors are screened very thoroughly for that.”

Screening also excludes donors with an increased risk of developing the diseases scientists are hoping to treat, such as metabolic syndrome related conditions.

A 2017 article published in Open Forum Infectious Diseases by Drs. Silverman and Burton found the cost of screening high numbers of potential donors could make establishing local programs extremely difficult, so having a central program such as the one in London could help patients in many regions.

In the study, only five of 46 potential donors passed the history, examination, blood, stool and urine tests, and of the five, four later travelled or had illnesses that made donation inadvisable.

The search continues in London for potential donors to help drive this research forward. You can read one donor’s story and learn how you can get involved here.

More on FMT and the microbiome:

Drugs vs. bugs: Harnessing the microbiome to improve treatments

Communications Consultant & External Relations

Lawson Health Research Institute

T: 519-685-8500 ext. ext. 64059

C: 226-919-4748

@email

The Best in Breast Care Conference

On Oct. 15, 2016, the Breast Care Program of St. Joseph’s Health Care London will be hosting the first annual Best in Breast Care Conference, which will feature leading experts in breast screening, diagnosis, treatment, reconstructive surgery, research, support, and survivorship.

Open to health professionals, students/trainees and the general public, this group learning program meets the certification criteria of the College of Family Physicians of Canada and has been certified by Continuing Professional Development, Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry for up to 6.25 Mainpro+ credits.

When: Oct. 15, 2016, 8:00 am to 4:00 pm

Where: Best Western Lamplighter Inn, London, ON

Host: Presented by St. Joseph’s Health Care London, Supported by ONERUN

Keynote address: Surgical oncologist Dr. May Lynn Quan, University of Calgary, will present on improving outcomes for young women with breast cancer.

For the full agenda and to register, visit www.sjhc.london.on.ca/breast-care-conference.

The children of Masiphumelele Township

Written by Dr. Gregor Reid, scientist at Lawson and professor at the Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry, Western University

Just off the main road from Cape Town, South Africa to Simon’s Town, sits Masiphumelele Township where challenges of poverty, malnutrition, HIV and the risk of violence face people every day.

It is also the location for the Desmond Tutu HIV Foundation Youth Centre, a safe haven that provides adolescent-friendly sexual and reproductive health services alongside educational and recreational activities for youth living in Masiphumelele and surrounding areas.

To understand some of the dangers that children face, in 2017 about 270,000 people in South Africa were newly infected with HIV, adding to one of the highest HIV prevalence rates in the world. The Tutu Youth Centre aims at helping educate youth to reduce their risk of becoming another HIV statistic.

I was invited there by University of Cape Town Professor Jo-Ann Passmore, a woman not only recognized for her research but whose passion for helping others is reflected in her warm smile (fourth from left in the below group photo). She asked if I would be interested in holding a workshop to illustrate to the youth how using sachets of probiotic bacteria could empower them. I jumped at the chance. On an afternoon break from the Keystone Symposium, thirty researchers joined me along with Jo-Ann and my wife Debbie, a teacher of children with learning disabilities.

After a tour of the areas where children learn on computers, play games in safety, or have personal discussions about sexual health, everyone filled the room with a stunning backdrop of the Nobel Laureate’s image. Having been privileged to meet the Archbishop when he was hosted by St. Joseph’s Health Care Foundation in 2008, it was a nerve-tingling experience.

Giving a lecture on beneficial microbes is hard enough to peers sitting in the back of the room, but to do so with young South Africans was somewhat more daunting. However, it proved to be a lot of fun especially when we had to identify kids who were good leaders (the boys all pointed to a girl), at making stuff and selling it to others (two boys stood out). By the end, we had picked the staff of a new company.

The next step was for four groups to go and decide on the company’s name, what products they’d make from the probiotic sachets (the options were many from yoghurt to cereals, juices and maize), what marketing tools they would use and who they would target to obtain a respectable income.

Interestingly, several of the conference participants seemed less engaged, as if they had never considered how microbiology research could affect real lives. In front of them were children facing huge challenges on a day-to-day basis. In one group, the kids were quiet until my wife brought out pens and paper, then they went to town designing products, names and labels. A lesson for me on how different people need different stimuli to become engaged. The faculty left early to beat the traffic back to Cape Town, so unfortunately, they did not hear the outcome of the children’s work.

When we re-assembled to present the results, I was impressed with what could be created in such a short time. My favourite was the Amazing Maize, a bottle shaped like a corn cob. It emphasized the importance of marketing and for products to taste and look good to be purchased.

It had been over ten years since Archbishop Tutu had applauded us for the Western Heads East project, and thanked us for empowering women and youth and contributing to nutrition in Africa. Since then, thanks to the huge efforts of Western University staff and students, and more recently IDRC funding and partnerships especially with Yoba-for-life, Heifer International and Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology, over 260,000 people in east Africa are now consuming probiotic yoghurt every week. The children of the South African townships were maybe too young to join in this new wave of microenterprises, but at least now they have heard about it and the importance of fermented food and beneficial bacteria.

In the background of the workshop several wonderful women committed to start up a new production unit. I left them some sachets to try out the process.

But it was me who left with the biggest lesson on how precious each life is, and how those of us with the knowledge need to provide the means for others to use their own talents to fulfill the purpose that their lives surely have.

No better way than to start with the children.

Gregor Reid PhD MBA FCAHS FRSC

Scientist, Lawson Health Research Institute, and Professor, Western University

London, Canada

The invisible world inside us

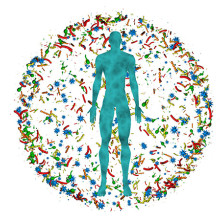

The human microbiome is a wonder of nature.

Trillions of microbes call our body home. They live in our gut and many other places throughout our body. They are involved in virtually every aspect of how we function and we are learning that they are essential to staying healthy. An unhealthy microbiome has been linked to many diseases from allergies to cancer and even mental health.

Most people out there have heard about probiotics and fermented foods, and chances are you’re trying to get more of them in your diet.

Drinking kombucha or eating yogurt, anyone?

Join Lawson Health Research Institute for our next Café Scientifique event, "The invisible world inside us: Exploring the human microbiome."

Hear from a panel of researchers who are unraveling the mysteries about the microbiome and using that knowledge to improve health and health care. They will also bust some myths and share the important facts when it comes to probiotics, prebiotics and the microbiome.

Image

SPEAKERS

- Dr. Gregor Reid, Lawson Scientist and Professor of Microbiology & Immunology and Surgery at Western University.

Presenting: Probiotics and Prebiotics - Look beyond the fake news - Dr. Michael Silverman, Lawson Associate Scientist, Chair of Infectious Diseases, Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry at Western University and Chief of Infectious Diseases for St. Joseph’s Health Care London and London Health Sciences Centre.

Presenting: Fecal Transplants: What does this crap have to do with me? - Dr. Jeremy Burton, Lawson Scientist and Assistant Professor of Surgery (Urology) and Microbiology & Immunology at Western University.

EVENT DETAILS

Date: Wednesday, November 27, 2019

Time: 7-9 pm (doors open at 6:30 pm)

Location: Best Western Plus Lamplighter Inn & Conference Centre (Regency Room), 591 Wellington Rd, London, ON N6C 4R3

Map and directions.

Parking: Free on-site parking

This is a free event and online registration is REQUIRED.

Registration for this evengt is now FULL.

Please fill out the form here to be added to the waitlist.

You will be notified should a spot open up.