Search

Search

Generation Vape: The new era of lung injury

One in four high school students have tried vaping in the past 30 days. Some believe that it’s a safe alternative to smoking, but is that true? Do we know enough about the risks? Hear the latest from a panel of experts and join the conversation about the health effects of vaping.

Presented in partnership with Western University's Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry, this community event includes a series of small presentations followed by a panel discussion. This includes the team that published the first reported case of vaping-related lung injury in Canada.

Speakers include:

- Dr. Karen Bosma, Critical Care Specialist, London Health Sciences Centre, Associate Scientist, Lawson Health Research Institute and Associate Professor, Department of Medicine, Schulich Medicine & Dentistry, Western University

- Grace Parraga, PhD, Scientist, Robarts Research Institute and Professor, Medical Biophysics, Schulich Medicine & Dentistry, Western University

- Carly Weeks, Health Reporter, The Globe and Mail

- Suraj Paul, Aliana Manji, and Eleanor Park, Human Environments Analysis Laboratory Youth Advisory Council (HEALYAC)

Event Details

- Date: Tuesday, March 10, 2020

- Time: 7:00 - 8:30 p.m. (Doors open at 6:00 p.m.)

- Location: Lecture Theatre, Museum London (421 Ridout St N)

- Registration: This event is free for all to attend, but registration is required.

Register today at

westernconnect.ca/generationvape.

Genetic testing could personalize care for patients with Crohn’s disease, particularly women

LONDON, ON - In a study involving 542 Crohn’s disease patients, researchers at Lawson Health Research Institute examined whether a patient’s DNA can be used to identify their risk of severe disease. They found that patients with a genetic variant in a gene called FXR (farnesoid X-receptor) are much more likely to need surgery and to need it earlier in their care journey. Surprisingly, they found that women with the genetic variant are at an even higher risk than men.

Crohn’s disease is an often debilitating condition that affects one in every 150 Canadians. The condition is characterized by intestinal inflammation caused by unnecessary attacks from the body’s immune system. It’s a disease that can behave and progress differently from one person to the next, with some requiring surgery to remove affected parts of the intestine.

“While medications are prescribed to manage Crohn’s disease, physicians have to balance the risk of side effects with the risk of undertreating severe cases of the disease,” explains Dr. Aze Wilson, Associate Scientist at Lawson Health Research Institute and Gastroenterologist at London Health Sciences Centre (LHSC). “In order to personalize treatment, it would be great to have a tool for identifying which patients will have the most severe cases of illness.”

Dr. Wilson and her colleagues became interested in the FXR gene because of its role in intestinal health. The FXR gene is a part of human DNA that controls how we process drugs and has also been linked to how well our intestines work. The research team suspected that variation in the gene could lead to poorer outcomes in Crohn’s disease patients.

“Given the importance of FXR to intestinal health, we wanted to see whether it plays a role in disease severity and we discovered that it does,” says Dr. Wilson. “Our findings suggest that genetic testing could be used to identify patients at a high risk of poor outcomes. This would allow physicians to tailor treatments to give patients the best chance at success.”

The team also discovered that women who carried the genetic variant were at the highest risk of needing surgery and the highest risk of early surgery, even when compared to men with the genetic variant. Struck by this finding, they conducted further testing using laboratory-based cell models. They found that estrogen (a female sex hormone) in combination with the genetic variant reduced the function of FXR even further.

“Differences between men and women with Crohn’s disease are not often considered in research or clinical practice. We apply treatments in the same way to both sexes, which may not be the best approach,” explains Dr. Wilson. “We identified a group of women who may benefit from a different approach to care. The study highlights the need for evaluating the effect of biological sex on disease and the interaction it may have with our DNA.”

Looking forward, the team hopes to further explore the effect of this genetic variant on intestinal health using laboratory-based cell models. They also hope to assess the value of genetic testing as a tool for informing treatment decisions made by patients and their physicians.

“One of our larger goals as a research group is to develop a personalized care plan for patients with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis – one that integrates genetic information and other biomarkers to improve how care is delivered to these patient populations,” notes Dr. Wilson.

The study, “Genetic variation in the farnesoid X-receptor predicts Crohn’s disease severity in female patients,” is published in Nature’s Scientific Reports.

-30-

DOWNLOADABLE MEDIA

Lawson Health Research Institute is one of Canada’s top hospital-based research institutes, tackling the most pressing challenges in health care. As the research institute of London Health Sciences Centre and St. Joseph’s Health Care London, our innovation happens where care is delivered. Lawson research teams are at the leading-edge of science with the goal of improving health and the delivery of care for patients. Working in partnership with Western University, our researchers are encouraged to pursue their curiosity, collaborate often and share their discoveries widely. Research conducted through Lawson makes a difference in the lives of patients, families and communities around the world. To learn more, visit www.lawsonresearch.ca.

Senior Media Relations Consultant

Communications & Public Engagement

T: 519-685-8500 ext. 73502

Celine.zadorsky@lhsc.on.ca

Get Involved

Clinical research participants make medical progress a reality.

Clinical research plays a crucial role in advancing medical knowledge. It is the key to improving health and the quality of care received by Ontarians, Canadians and people worldwide.

Current clinical trials

Visit the following registries to find other current clinical trials being conducted at Lawson Health Research Institute:

- For all types of clinical trials: www.clinicaltrials.gov

- For cancer clinical trials: www.ontariocancertrials.ca

- Clinical Trials Finder by Clinical Trials Ontario: http://trial-finder.ctontario.ca/

Additional resources:

- Health Canada’s clinical trials database

- World Health Organization

- International Standard Registered Clinical/soCialsTudy Number (ISRCTN)

Why should you participate in a clinical research study?

- Contribute to important health research and innovation.

- Help yourself and others by advancing medical knowledge and patient care.

- Access cutting-edge diagnostics and treatments.

- Gain additional support and care from a clinical research team.

Will you help shape the treatments of tomorrow? Watch this video from It Starts With Me to learn more about clinical trials, a type of clinical research:

As it marks its 10-year anniversary, Clinical Trials Ontario recently had Ontario health leaders reflect on the vital role of clinical trials, including Lawson Health Research Institute's Scientific Director David Hill.

And those leaders expressed their thanks to the community, which plays a vital role in advancing health research.

For more information visit our Clinical Research page.

Global initiative aims to prevent falls in older adults

Chaired by Dr. Manuel Montero-Odasso, Scientist at Lawson Health Research Institute, a group of 96 experts from 39 countries and 36 societies and agencies in Geriatric Medicine and Aging have come together to develop the “World Guidelines for Falls Prevention and Management for Older Adults: A Global Initiative.”

Published in Age and Ageing, the official journal of the British Geriatric Society, the guidelines provide recommendations to clinicians working with older adults to identify and assess fall risks.

“The global population is aging. Thanks to social and medical advances, some chronic conditions are diminishing proportionally. This is not the case for falls,” says Dr. Montero-Odasso, who is also a Geriatrician at St. Joseph’s Health Care London’s Parkwood Institute and a Professor at Western University’s Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry. “Unfortunately, falls and related injuries among older adults are increasing and there is no sign of future decline.”

With new evidence and studies released since previous guidelines were published more than a decade ago, experts felt it was the right time for an update and an opportunity to incorporate a worldwide perspective

“Besides the rigorous methodology that 11 international working groups followed to provide new meta-analyses, including several new Cochrane collaborations, this World Falls Guidelines are, to the best of our knowledge, the first clinical practice guidelines in fall prevention to include a panel of older adults with lived experience in falls and mobility problems,” says Dr. Montero-Odasso. “They provided feedback, comments and opinions on our recommendations, making them considerably better and with wider applicability.”

Some key themes in the recommendations include:

- Falls can be prevented, but it requires multidisciplinary management.

- Preventing falls has wider benefits for quality of life.

- Fall risk can be assessed by trained clinicians with simple resources.

- A combination of interventions, including specific exercises to improve balance and strength, when delivered correctly, can effectively reduce fall risk in older adults.

Dr. Montero-Odasso says there was enough evidence to suggest that a global approach is needed to prevent falls in older adults and that “low risk does not mean no risk.” Even active older adults who are low risk should work on preventing loss of mobility and falls.

The next steps are for the guidelines to continue obtaining formalized endorsement of all the groups involved in the initiative and then for the guidelines to be fully implemented.

You can read the full guidelines here.

Communications Consultant & External Relations

Lawson Health Research Institute

T: 519-685-8500 ext. ext. 64059

C: 226-919-4748

@email

Global study on heart valve repair surgery will improve patient outcomes around the world

Leaking valves are a common condition amongst cardiac patients

MEDIA RELEASE

For immediate release

LONDON, ON- Researchers at Lawson Health Research Institute and Western University had a leading role in a new global study that will change the way surgeons repair leaky valves in the heart. It’s one of the most common heart valve conditions, where many patients don’t even realize they have a leaky valve and are asymptomatic, often presenting to doctors once they are late stage into the disease.

“If the leak in the mitral valve is not repaired, a patient will have problems with fluid retention, shortness of breath and heart failure,” Says Dr. Michael Chu, Lawson Scientist and Chair/Chief of the Division of Cardiac Surgery at Western’s Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry. “That will then lead to complications requiring hospitalization and eventually an increased risk of death.” Dr. Chu is also a cardiac surgeon at London Health Sciences Centre (LHSC).

There are two related valves in the heart that can potentially leak and lead to further complications, the mitral valve and the tricuspid valve. Traditionally, the mitral valve is surgically repaired first, with the belief that it will lead to improvements in the tricuspid valve, however, scientists have discovered that isn’t always the case. “What we were concerned with was, if we repair the mitral valve only, will the tricuspid valve still leak?”

To answer that question, the Division of Cardiac Surgery research team engaged in a multicenter, randomized trial run by the Cardiothoracic Surgical Trials Network, an important clinical trials network from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute in the United States. The study took place in 39 hospital sites across the world with more than 400 cardiac patients. Dr. Chu and his team in London worked with patients through LHSC to be the top recruiting hospital and research team in this study. Patients were randomized in the trial, half receiving mitral valve repair alone, and half receiving mitral and tricuspid repair surgery at the same time.

“What we found two years after the operations was that the group that had both mitral and tricuspid repair had significantly less severe residual leak of the tricuspid valve,” explains Dr. Chu. “These findings suggest that concomitant tricuspid repair is extremely effective and those patients who present with a tricuspid leak, should have both valves repaired at the same time.”

The study findings have been published in the New England Journal of Medicine, which has a high impact worldwide within the medical community, especially when it comes to medical practices. Dr. Chu, joint first author in the paper, believes these findings will have an important impact worldwide to how surgical teams repair leaking heart valves, and is extremely proud that this top tier, practice-changing research is being performed at Western’s Schulich School of Medicine and LHSC.

Moving forward, the next steps will be to follow these patients for five years and further investigate various aspects of the study, with the ultimate goal of improving long term outcomes for patients.

-30-

Lawson Health Research Institute is one of Canada’s top hospital-based research institutes, tackling the most pressing challenges in health care. As the research institute of London Health Sciences Centre and St. Joseph’s Health Care London, our innovation happens where care is delivered. Lawson research teams are at the leading-edge of science with the goal of improving health and the delivery of care for patients. Working in partnership with Western University, our researchers are encouraged to pursue their curiosity, collaborate often and share their discoveries widely. Research conducted through Lawson makes a difference in the lives of patients, families and communities around the world. To learn more, visit www.lawsonresearch.ca.

Western delivers an academic experience second to none. Since 1878, The Western Experience has combined academic excellence with life-long opportunities for intellectual, social and cultural growth in order to better serve our communities. Our research excellence expands knowledge and drives discovery with real-world application. Western attracts individuals with a broad worldview, seeking to study, influence and lead in the international community.

The Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry at Western University is one of Canada’s preeminent medical and dental schools. Established in 1881, it was one of the founding schools of Western University and is known for being the birthplace of family medicine in Canada. For more than 130 years, the School has demonstrated a commitment to academic excellence and a passion for scientific discovery.

Senior Media Relations Consultant

Communications & Public Engagement

T: 519-685-8500 ext. 73502

Celine.zadorsky@lhsc.on.ca

Growing Tissues in the Lab

When challenged by surgeons to find better treatments for difficult-to-manage connective tissue diseases, Dr. David O’Gorman gladly accepted.

Dr. O’Gorman is a Molecular Biologist and Lawson Scientist based at St. Joseph’s Hospital, a part of St. Joseph’s Health Care London. His research focuses on understanding normal and abnormal connective tissue repair. He collaborates with researchers and clinicians working in many different disciplines, including those specializing in reconstructive surgery, orthopedics and urology.

Surgical reconstructions can be hampered by a lack of graft tissue, or graft tissue of insufficient quality, making it difficult to achieve optimal outcomes for the patients.

An example is a condition called urethral stricture disease (urethral scarring). This condition occurs in males and typically causes symptoms such as frequent and urgent urination, and slow urinary stream. In extreme cases, it can cause urinary tract infections, permanent bladder dysfunction and renal failure. Recurrence rates after minimally invasive treatments are high, and so many urologists recommend open surgical approaches.

Surgeons can use the patient’s own tissues to reconstruct the urethra after stricture removal. This tissue is normally sourced from the buccal cavity in the mouth but taking large tissue grafts can result in complications. In cases where buccal grafts have been used for previous reconstructions, there may not be enough intact tissue left.

Dr. O’Gorman sees a solution in growing sheets of human buccal tissues in the lab.

“We are currently using buccal graft trimmings as a source of cells, culturing them in a 3D environment and expanding them to create tissues of suitable size, density and elasticity.”

The patient’s own cells are used to generate a tissue graft for urethral reconstruction. While several research groups have developed this approach in the past, few have attempted to translate their models for clinical use.

“Our immediate goal is to provide proof of principle – that we can consistently generate grafts of suitable size and functional characteristics,” explains Dr. O’Gorman, “In the future, we could be providing bioengineered graft tissues for reconstructive surgeries here in London.”

Bioengineered human tissues can also be used as ‘mimetics’ – replications of human tissues – to study diseases, especially those difficult to model using routine laboratory methods.

Instead of a using a growth media or sterile plastic dishes, 3D cell culture is achieved by embedding cells in a matrix of proteins and other molecules normally found in those tissues. In this environment, gene expression and growth is more similar to cells of connective tissues in the body being replicated.

Dupuytren’s disease (or Dupuytren’s Contracture) affects the palmar fascia in the hand, a connective tissue beneath the skin that extends from the base of the palm into the fingers. This disease can be understood as a type of excessive scarring, where normal tissue repair processes have gone awry and dense scar tissue forms, typically causing permanent palm or finger flexion that restricts hand function.

This condition is surprisingly common and may affect more than one million people in Canada. While there are surgical treatment options available, none consistently prevent this disease from recurring in at least a third of patients.

“Due to its high recurrence rate after treatment, Dupuytren’s disease is currently considered incurable. Our challenge is to understand it well enough to develop truly effective treatments,” says Dr. O’Gorman.

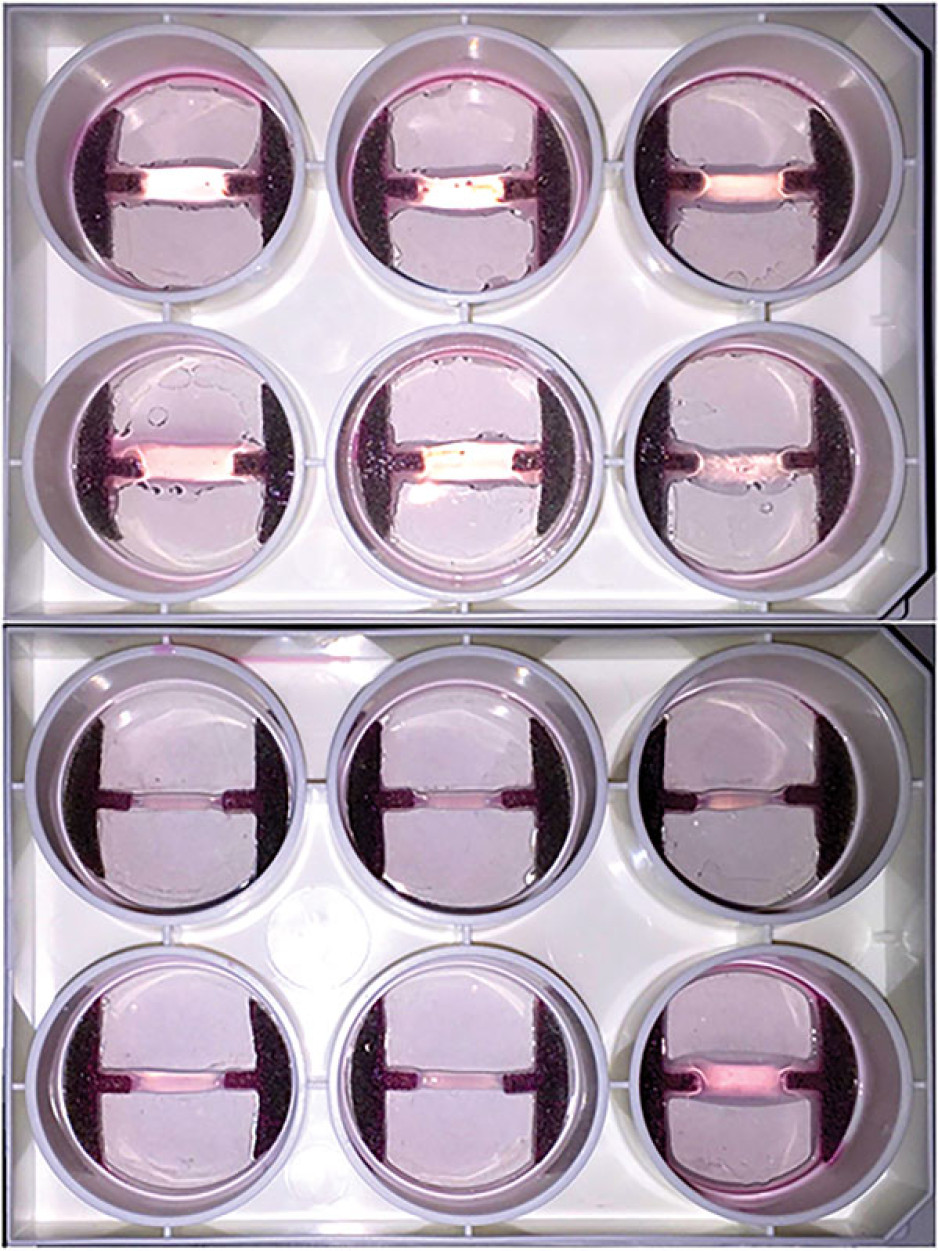

Human hands have unique characteristics not found in other species, making animal models impractical. Instead, Dr. O’Gorman’s team extracts cells from the diseased palmar fascia of patients undergoing hand surgeries and bioengineers them into palmar fascia ‘contractures’ in the lab.

“Since the cells from a single palmar fascia sample can be used to grow dozens of little contractures, we can test many different treatments simultaneously to see what works best for each patient.”

This approach may also allow them to determine if Dupuytren’s disease is truly one disease, or a group of similar diseases that cause palm and finger contractures.

“Often, Dupuytren’s disease is clearly heritable, but some individuals have no family history of it and develop apparently sporadic disease,” notes Dr. O’Gorman. “We want to determine if these are truly the same disease at the molecular level.”

Another major cause of abnormal connective tissue repair is infection, and tissue mimetics can play a role here, too. While rare, infections of artificial joint replacements are particularly devastating for patients, as they typically require readmission to hospital to remove the infected joint, weeks of antibiotic-based treatment, and an additional surgery to replace the artificial joint.

In addition to the associated pain and suffering, these procedures are technically challenging and costly to our health care system.

Artificial shoulder joint infections are most frequently caused by the microorganism Cutibacterium acnes (C. acnes). C. acnes infections disrupt normal tissue repair processes after surgery, cause shoulder tissues to die and promote loosening of the artificial joint. These infections are difficult to diagnose, and there is a lack of reproducible

models in which to study them. Dr O’Gorman’s team has set out to create the first human Shoulder-Joint Implant Mimetic (S-JIM) of C. acnes infection.

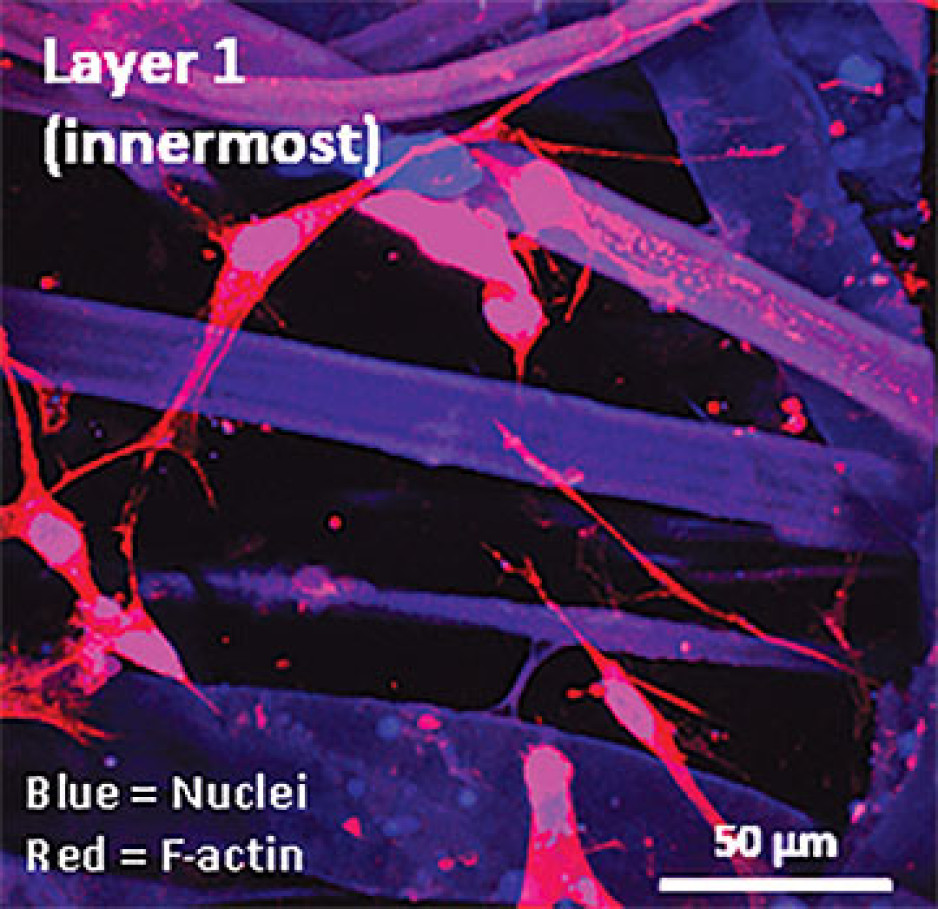

“While S-JIMs are more complex, they are 3D in vitro cell culture systems designed to mimic human tissues, like those that we use for studying Dupuytren’s disease.”

S-JIMs include layers of artificial human tissue, wrapped around cores of titanium alloy or cobalt chrome, the metals used to create artificial joints. They are co-cultured with C. acnes under low oxygen conditions similar to those that normally occur around artificial shoulder joints.

“We are bioengineering simple 3D cell cultures to more closely mimic the complexity of human tissues, with blood supply, nerves and interactions with other cells.” – Dr. David O’Gorman

Studying the connective tissue layers close to the infection allows researchers to investigate processes that promote infection, such as the formation of a biofilm that harbours and protects the bacteria from the body’s immune system. They are also able to test whether novel treatments can disrupt biofilm formation and increase the effectiveness of antibiotics.

Dr. O’Gorman predicts that in the future, medical researchers will routinely use bioengineered 3D human tissue and organ mimetics to accelerate our understanding of disease.

“The technology is in its infancy, but the potential for using bioengineered human tissues for surgical reconstructions or as disease models is huge. At Lawson, we’re ready to take on health care challenges and build on innovative approaches to improve the quality of life for patients.”

ONLINE EXCLUSIVE: What is 3D cell culture?

Medical researchers have grown human cells in culture media on or in sterile plastic dishes, such as Petri dishes, for more than 50 years.

Some cells, such as blood cells, can survive and grow in suspension, while others like smooth muscle cells need¬ to adhere to a surface to survive and grow. These are often called “2D cell cultures” because the cells grow horizontally across the bottom of the dish.

Some cells derived from connective tissues, such as fibroblasts, are not only adherent, but also very sensitive to the stiffness of their environment (“biomechanically sensitive” cells). Plastic dishes are at least 10,000 times stiffer than most connective tissues, and when biomechanically sensitive cells detect stiff surfaces, they can change the expression of their genes and behave abnormally.

The most common proteins in these tissues - and in the entire human body - are collagens, and one routine 3D cell culture approach is to embed fibroblasts in a collagen gel (gelatin). Fibroblasts in this environment can grow in any direction they choose, and their gene expression is more similar to cells in connective tissues.

These simple 3D cell cultures represent tissue engineering in its most basic form.

“Our challenge is to bioengineer simple 3D cell cultures in the lab to more closely mimic the complexity of human tissues, which have blood supply, nerves and interactions with other cells and tissues that modify their function and ability to heal after injury,” explains Dr. O’Gorman.

Dr. David O’Gorman is a Lawson Scientist and Co-director, Cell and Molecular Biology Laboratory at The Roth | McFarlane Hand and Upper Limb Centre in London, Ontario. He is also an Assistant Professor at Western University.