Search

Search

COVID-19 shown to leave unique lung fingerprint

LONDON, ON – Researchers at Lawson Health Research Institute (Lawson) developed and tested an artificial neural network for diagnosing COVID-19. The AI system was trained to learn and recognize patterns in ultrasound lung scans of patients with confirmed COVID-19 infection at London Health Sciences Centre (LHSC) and compared them to ultrasound scans of patients with other types of lung diseases and infections.

“The AI tool that we developed can detect patterns that humans cannot. Lung ultrasound scans of patients with COVID-19, as well as other lung diseases, produce a highly abnormal imaging pattern, but it is almost impossible for a physician to tell apart different types of infections by looking at these images. There are details, however, that distinguish COVID-19 at the pixel level that cannot be perceived by the human eye,” explains Dr. Robert Arntfield, Lawson Researcher and Medical Director of the Critical Care Trauma Centre at LHSC.

“The neural network was able to identify the unique characteristics among different scans, and exceed human-level diagnostic specificity. Our study of over 100,000 ultrasound images showed that while trained physicians could – as expected - not distinguish between different causes of lung disease, the AI had nearly perfect accuracy in making the diagnosis. It’s almost like the AI sees a QR code that we cannot see, unique to the disease.”

LHSC is a global leader in the use of point-of-care ultrasound. It has become an important tool for the diagnosis and care of critically ill patients experiencing acute respiratory failure. The convenience, portability and low cost of using these machines makes them ideally suited for pandemic conditions.

This study is part of a collaborative effort by a small group of local clinicians driven to innovate and create technology that solves complicated problems with AI. “There are a lot of brilliant minds in our city, and I’m very proud that we were able to rapidly pull together a local team to design, develop and test a complex idea,” says Dr. Arntfield. “We are already expanding on these findings with more research.” Lawson has recently approved Dr. Arntfield’s “Project Deep Breathe” which aims to go beyond COVID-19 and explore multiple conditions where lung ultrasound and AI can be paired together.

The study, “Development of a convolutional neural network to differentiate among the etiology of similar appearing pathological B lines on lung ultrasound: a deep learning study”, is published in BMJ Open.

-30-

Lawson Health Research Institute is one of Canada’s top hospital-based research institutes, tackling the most pressing challenges in health care. As the research institute of London Health Sciences Centre and St. Joseph’s Health Care London, our innovation happens where care is delivered. Lawson research teams are at the leading-edge of science with the goal of improving health and the delivery of care for patients. Working in partnership with Western University, our researchers are encouraged to pursue their curiosity, collaborate often and share their discoveries widely. Research conducted through Lawson makes a difference in the lives of patients, families and communities around the world. To learn more, visit www.lawsonresearch.ca.

Senior Media Relations Consultant

Communications & Public Engagement

T: 519-685-8500 ext. 73502

Celine.zadorsky@lhsc.on.ca

Cyclotron hits 10,000-bombardment milestone

Cyclotron staff at St. Joseph’s Health Care London have recorded a 10,000-mark milestone in the same understated way they work every day to improve patient care and cutting-edge research.

No balloons, no streamers, no fanfare: Just an efficient note atop a printout as the bombardment number spun past 9,999 in the early hours of Dec. 31.

“It’s taken us 15 years to get to this point and our work continues to grow,” says Michael Kovacs, PhD, Lead of Lawson’s Nordal Cyclotron & PET Radiochemistry Facility and Leader of the Imaging Research Program at Lawson Research Institute, the innovation arm of St. Joseph’s.

“The numbers are great but the real satisfaction is knowing every single bombardment means something important to a patient or a researcher working towards better patient health.”

St. Joseph’s GE PETtrace cyclotron is a particle accelerator that produces radioisotopes for use in positron emission tomography (PET) scans across Southwestern Ontario, from Windsor to Toronto. It is a vital tool for ultra-precise cancer diagnoses and for advanced research into scores of diseases.

In patient care, each “bombardment” – a grouping of radioisotopes that are then lab-processed, tested and made into smaller batches – can be used to aid cancer scans for as many as 25 people.

“A precise scan can make a dramatic difference, a life-changing difference, in how someone’s cancer is diagnosed and custom-managed,” Kovacs says. “If we think of the PET scanner as the engine of that transformative work, the cyclotron’s radioisotopes are its rocket fuel.”

Isotopes injected into patients are designed to have a short radioactive half-life – between two minutes and 110 minutes – which is another reason St. Joseph’s cyclotron is such an asset for timely care in the region.

“You can’t store or stockpile them. You have to use them almost immediately, so it’s essential to local and area hospital centres to have a ready, reliable source nearby,” Kovacs says.

About half the batched bombardments are used in patients to help with clinical diagnoses that will guide doctors’ treatment decisions.

The other half are used for research trials and pre-clinical research through Lawson, in fields as diverse as oncology, cardiology, neurology, psychiatry, metabolic disease and infectious diseases. In one promising study, for example, they’re being used to image specific brain proteins as researchers explore new disease-modifying treatment pathways for Alzheimer disease.

The next burgeoning field, Kovacs says, is theranostics: the science of diagnosing cancer and precision-attacking it at the same time. “That’s exciting for me, to be able simultaneously to see what we treat and treat what we see.”

About 15 highly specialized staff work at St. Joseph’s cyclotron facility, plus PhD-candidate researchers and other trainees.

Generous donors through St. Joseph’s Health Care Foundation have made much of this advanced research and next-level technology a reality. During the past few years, the Foundation granted nearly $800,000 in donor support to fund extensive renovations to the facility, making it possible to increase production of isotopes and expand life-saving care. Recently, $1 million in donations supported a new PET/CT scanner – the heart of Canada’s first national GE centre of excellence in molecular imaging and theranostics being developed at St. Joseph’s Hospital.

“We know the cyclotron is a critical tool in our imaging work and we are grateful to those donors who stepped up to help us with renovations that enabled the doubling of our facility’s production capability,” says Michelle Campbell, President and CEO of St. Joseph’s Health Care Foundation. “This renovation helps keep St. Joseph’s imaging program at the cutting edge of clinical care.”

The 40-tonne, room-sized cyclotron is more than a machine, and more than the experts who process, test, ship and use the radioisotopes, Kovacs notes.

It’s also testament to the vision of St. Joseph’s long-time chief medical physicist Frank Prato, PhD, and to the support of hospital administrators who saw its need and potential, he adds.

“We are innovators, and our vision is that we’re going to expand St. Joseph’s imaging expertise on an even larger world stage,” Kovacs says.

Dementia research hits the ‘mark’

St. Joseph’s Health Care London is at the forefront of national research exploring biomarkers to better predict dementia and slow its onset.

Dr. Michael Borrie is now seeing grandchildren of patients who came to his clinic when he first started Alzheimer’s research 30 years ago.

His message to this new generation is more hopeful than ever, bolstered by ever-more-reliable ways of early detection and being tantalizingly close to a future of predicting dementia and intervening even before symptoms appear.

“The ultimate goal is to slow cognitive decline – and to stop it if we can – so that people can live independently, and happier, for a lot longer,” says Borrie, Medical Director of the Aging Brain and Memory Clinic at St. Joseph’s Health Care London (St. Joseph’s).

“We’re aiming to alter the trajectory of dementia,” he says.

A geriatrician, clinician and researcher, Borrie is also Platform Lead for the Comprehensive Assessment of Neurodegeneration and Dementia (COMPASS-ND), a long-term study within the Canadian Consortium on Neurodegeneration and Aging (CCNA).

Recently, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research announced $20.6 million in funding to continue the work of CCNA, a 30-site, multi-pronged project of which the St. Joseph’s-based team is the lead player. The grant will enable them to advance the frontiers of dementia research to benefit real-world patients here and across the country.

Solving mysteries with biomarkers

Despite the prevalence of Alzheimer’s and other neurodegenerative diseases – and with more than 10,000 new diagnoses in Canada each year – there are still many mysteries to solve: Why do some people have early-onset dementia while others, super-agers, remain alert and active in their 90s? What’s happening genetically, in their environment and personal medical history to advance or protect against the disease?

What is known, however, is the link between damaged nerve cells and specific proteins that misfold and clump together to form amyloid plaques and tau tangles in the brain. Detecting these abnormal proteins early is an important key to diagnosis and prediction.

Locally, the most comprehensive tool has been state-of-the-art brain Positron Emission Tomography (PET) scanning at St. Joseph’s Imaging. Lawson researchers are also involved in reliably detecting amyloid proteins by analyzing participants’ cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) – a surprisingly accurate way of confirming imaging results, says geriatrician Dr. Jaspreet Bhangu, a Lawson scientist and head of the biomarker project.

Through the BioMIND regional research project, Lawson scientists are analyzing PET scans, blood and CSF samples to check for specific protein biomarkers. If shown to be reliable, a series of these tests over time could signal whether the disease is progressing, and could predict whether it will progress or respond to treatment.

All that gets added to an arsenal that includes tests of behaviour, memory and cognitive function.

“It’s a triple assessment, or even a quadruple one, that we can conduct over time. We hope to use these advanced tests to provide vital information, similar to what is done in certain types of cancer,” Bhangu says.

But that’s not all.

Testing potential treatments

St. Joseph’s is also one of the country’s most active sites for clinical trials into whether novel medications might be able to directly pinpoint and destroy the proteins that cause Alzheimer disease.

“This is the intersection of cutting-edge research, top-notch resources and excellent clinical practice to develop personalized treatments,” says Bhangu. “What makes us unique in Canada among dementia researchers is that our science is taking us from bench to bedside – a rapid turnaround from research to direct patient benefit.”

If a person has a strong family history of Alzheimer disease and no symptoms – but does have positive biomarkers confirming presence of disease – they may then choose to take part in a randomized controlled trial to try to alter the trajectory of the disease.

“It’s still in a research context, still in clinical trials – but if Health Canada ultimately approves a treatment, we’ll have the ability and the patient database to be able to translate our findings into clinical practice much more quickly instead of waiting for years,” says Borrie.

All this is good news for a generation eager for answers, Borrie says.

“When we learn more about the mechanisms of the disease, we can find more effective, earlier treatments. And if we can treat people earlier, we hope to move the disease progression curve to the right, to add more years of good cognitive health to someone’s life.”

Detecting prostate cancer with a drop of blood and Gulf War technology

London, Ontario - Gulf War technology is making it possible for researchers to detect prostate cancer with a single drop of blood.

Hon Leong, PhD, assistant professor at Western University’s Schulich School of Medicine and Dentistry and scientist at Lawson Health Research Institute, and his team have repurposed a machine once used to detect airborne pathogens in the second Gulf War. The machine is now used for fluid biopsies – a non-invasive way to detect prostate microparticles in the blood in a matter of minutes. Microparticles are essentially garbage released by prostate cells that circulate throughout the bloodstream.

Most men who are more than 40 years old, regardless of their health, have detectable levels of prostate microparticles in their bloodstream. Leong’s research is the first clinical cancer research project to correlate the number of microparticles in the blood to the risk of having prostate cancer – the more microparticles, the higher the risk.

Used in the Gulf War, and more commonly to test water purity, the machine uses flow cytometry to detect microparticles. Flow cytometry measures the specific characteristics of a fluid, such as blood, as it passes through a laser.

Leong’s research provides a more accurate and less invasive testing method for patients suspected of having prostate cancer, and helps to identify patients who are at a higher risk of dying from prostate cancer.

Current methods of detecting prostate cancer, such as the prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test and biopsies, have limitations. PSA tests are based on measuring a specific protein released by the prostate gland, but do not provide a definitive diagnosis. A physical exam and biopsy are needed if PSA levels are elevated. However, even the painful biopsy procedure has a 15 per cent error rate. During biopsies, a painful and invasive procedure, 12 needles are inserted into the rectum, with the hope of extracting material from an area with a tumour.

“Our findings point to a new direction in how we can better identify patients who actually have prostate cancer,” said Leong. “With this test, we can improve the clinical outcomes for patients, reducing costs for unnecessary procedures and reducing errors in diagnosis.”

- 30 -

See all Lawson Media Releases

Western delivers an academic experience second to none. Since 1878, The Western Experience has combined academic excellence with life-long opportunities for intellectual, social and cultural growth in order to better serve our communities. Our research excellence expands knowledge and drives discovery with real-world application. Western attracts individuals with a broad worldview, seeking to study, influence and lead in the international community.

Lawson Health Research Institute is one of Canada’s top hospital-based research institutes, tackling the most pressing challenges in health care. As the research institute of London Health Sciences Centre and St. Joseph’s Health Care London, our innovation happens where care is delivered. Lawson research teams are at the leading-edge of science with the goal of improving health and the delivery of care for patients. Working in partnership with Western University, our researchers are encouraged to pursue their curiosity, collaborate often and share their discoveries widely. Research conducted through Lawson makes a difference in the lives of patients, families and communities around the world. To learn more, visit www.lawsonresearch.ca.

Senior Media Relations Consultant

Communications & Public Engagement

T: 519-685-8500 ext. 73502

Celine.zadorsky@lhsc.on.ca

Detecting the Undetectable

A simple fall can lead to long-term hand problems such as arthritis due to fracturing the scaphoid bone in the wrist. Scaphoid fractures are known to have the highest rate of healing failures. While this bone’s fragile blood supply is commonly thought to be the main reason for why it is difficult to heal, Dr. Ruby Grewal is looking into a different reason – infection.

Infections are known to cause difficulty in healing bones, but traditional tests for infections in the scaphoid have come up negative. With new advancements in detecting microbial DNA, scientists can now test for ‘clinically undetectable’ infections.

In a new study, Dr. Grewal will use microbial DNA test whether or not there are infections in the scaphoid fracture which causes improper healing of the bone.

“The goal of this study is to use advanced DNA sequencing technology to test whether or not we can detect evidence of microorganisms in non-healing scaphoids,” explains Dr. Grewal, Lawson Scientist and Orthopaedic Surgeon at the Roth McFarlane Hand and Upper Limb Centre (HULC) at St. Joseph’s Health Care London.

Finding new causes of improper healing of the scaphoid bone could improve treatments for individuals with these injuries and prevent long-term problems with hand function. These insights into the causes of improper healing could also prevent young patients from developing wrist arthritis.

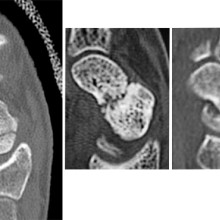

From left to right: Normal scaphoid fracture. Scaphoid fracture that is struggling to heal. Scaphoid non-union where the bone has failed to heal.

Dr. Grewal’s study is being funded through the Lawson Internal Research Fund (IRF).

“The financial support provided by Lawson’s IRF is of utmost importance to researchers. These funds will allow our team to embark on a new area of research and test a novel hypothesis,” says Dr. Grewal, “While traditional granting agencies are reluctant to fund completely novel areas of research without pilot data to prove feasibility, the Lawson IRF allows researchers to investigate new theories in a sound scientific manner. Without the ability to test new ideas we cannot innovate and make advancements in health care. Support for this project allows for that.”

Lawson’s IRF is designed to provide Lawson scientists the opportunity to obtain start-up funds for new projects with the potential to obtain larger funding, be published in a high-impact journal, or provide a clinical benefit to patients. Funding is provided by the clinical departments of London Health Sciences Centre and St. Joseph’s Health Care London, as well as the hospital foundations (London Health Sciences Foundation and St. Joseph’s Health Care Foundation).