Finding solutions to a triple negative problem

For Dr. Armen Parsyan, clinical practice and scientific research are equally important components of his career.

This Armenia-born clinician-researcher studied at Boston University, Harvard University, the University of Cambridge, McGill University and the University of Toronto before landing at Western’s Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry. He’s currently an associate professor, head of the Parsyan Cancer Research Lab and a breast surgeon at St. Joseph’s Health Care London and London Health Sciences Centre (LHSC).

“My interest was not only to practice, but also to investigate,” he shares about what motivated him to enter this field. “With clinical work, there’s more practical decision making and you see the results of your work. But at the same time, breast cancer is still the second leading cause of cancer-related mortality in Canada for women. That triggers a personal battle for me.”

His research aims to advance breast cancer care by investigating cancer cells at the molecular level. One of his long-term projects is targeting one of the most aggressive types of breast cancer: triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC). This project is unfolding at the Parsyan lab, located in LHSC's Verspeeten Family Cancer Centre as part of London Health Sciences Centre Research Institute.

In 2024, he brought on a PhD student, Anayra Goncalves, to continue leading this vital research focused on better understanding TNBC. A Lawson Research Institute Internal Research Fund award, funded by donors through St. Joseph’s Health Care Foundation, helped make this stage of the study possible.

Fighting the odds

As cancer develops, it produces some molecules called biomarkers that clinicians use to determine a patient’s best treatment plan. But TNBC cells don’t have the three biomarkers commonly found in other breast cancer types: hormone receptors for estrogen, progesterone and an overexpression of the HER2 protein.

TNBC tends to grow and spread more quickly than other breast cancers and it’s more likely to recur. It becomes particularly dangerous when it spreads beyond the breast to lymph nodes in the armpit. When this happens, treatments like chemotherapy and surgery might be less effective, leading to poorer outcomes for patients.

That challenge inspired Dr. Parsyan to seek out potential new biomarkers for TNBC with the goal of helping people fight this type of cancer. “Research is about trying to find solutions to problems that you are sometimes powerless to, clinically,” he says.

The next frontier in breast cancer research

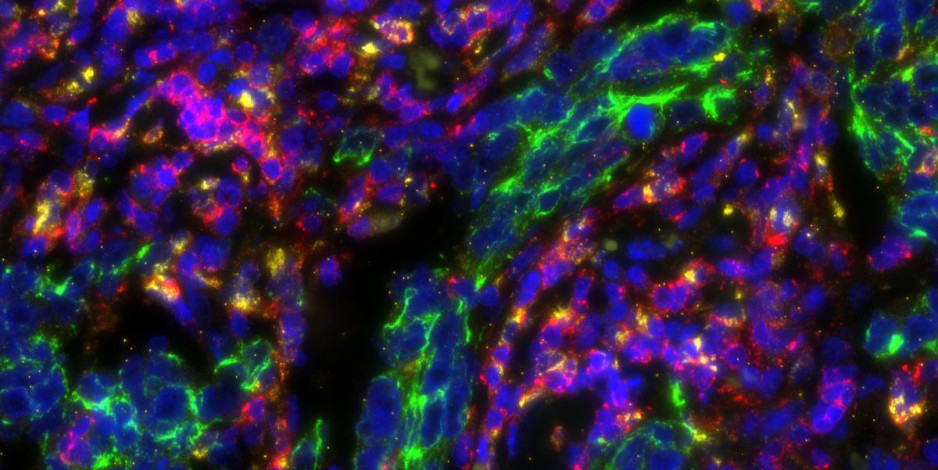

His research team is using spatial omics to analyze samples from breast cancer patients. Understanding the molecular changes that cause TNBC to spread could lead to more effective treatments and help prevent the cancer cells from spreading in the first place.

Spatial omics is a cutting-edge technology that preserves the tissue in the sample so that researchers can investigate cancer in its native “spatial” context and better understand the disease mechanisms. Spatial omics is widely regarded as one of the next frontiers in breast cancer research.

The team is studying samples from female patients with TNBC spread to the armpit lymph nodes who were treated in London. The spatial omics technology enables them to examine and map the changes in thousands of molecules produced by cancer cells and their surroundings in breast tissue. This helps them see which changes are connected to the spread of cancer and to treatment response. They have already made promising progress with preliminary data from a smaller group of patients.

An important contribution

Thanks to donor support through the IRF award, PhD student Goncalves has led the data analysis during the past year. “There's so much data to analyze,” Dr. Parsyan shares. “This was such an important contribution and we are really advancing.”

Their ultimate goal is to determine biomarkers that could lead to personalized care plans, new treatments and better outcomes for patients facing TNBC and their loved ones. “If you want to do innovative work, you have to take on board a high-risk, high-output project like this,” Dr. Parsyan says. “There’s a chance of failure. But if you succeed, you might find something really useful.”