Search

Search

Study aiming to slow cognitive decline in older adults gets $1.5M

LONDON, ON - Led by Dr. Manuel Montero-Odasso and his team at Lawson Health Research Institute, the first large-scale Canadian clinical trial using personalized lifestyle intervention delivered at home to help older adults with mild cognitive impairment is getting underway with support from a Weston Foundation grant of $1.5 million.

Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is an intermediate stage between the expected cognitive decline of normal aging and the more serious decline of dementia. There is growing evidence that enhancing physical activity, stimulating cognitive training and addressing cardiovascular factors could delay or prevent the decline to dementia.

Part of the Canadian Consortium on Neurodegeneration in Aging (CCNA), the SYNERGIC-2 trial will provide virtual at-home interventions to 550 study participants with MCI, including personalized one-on-one coaching, to help make lifestyle and behavioural changes. This trial builds upon the successful SYNERGIC-1 trial, which used face-to-face interventions, by delivering them remotely using digital technology.

These interventions will target five areas including physical exercise, cognitive training, diet recommendations, sleep interventions and vascular risk factor management, with the goal of enhancing health and maintaining independence for individuals at risk for developing dementia.

“There are important risk factors related to exercise, diet, sleep and socialization,” says Dr. Montero-Odasso, Lawson Scientist, Geriatrician at St. Joseph’s Health Care London’s Parkwood Institute and a Professor at Western University. “If we can make the brain a little healthier with multiple lifestyle interventions, we may be able to delay or even prevent dementia.”

The year-long study includes 35 researchers recruiting a diverse population of older adults with MCI across 10 Canadian cities. The research teams are currently looking for participants ages 60-85 with MCI and additional dementia risk factors.

Researchers have created a digital platform to deliver the interventions at home with effective coaching strategies that will help to overcome barriers to lifestyle interventions, like difficulty accessing intervention sites, lack of time to attend gym sessions or living in rural/remote areas.

“There are many Canadians who are at high risk of developing dementia, based on their family history and genetics,” explains Dr. Howard Chertkow, Chair of Cognitive Neurology and Innovation at Baycrest Health Sciences, Scientific Director at CCNA and a co-investigator on the study. “Other risk factors include having high blood pressure and diabetes. We have seen that we can reduce the risk of getting dementia if we can get people to improve their lifestyles in multiple ways.”

Those interested in taking part in the study can contact @email for additional details.

The study is part of a global initiative known as World-Wide FINGERS, an interdisciplinary network working on the prevention of cognitive impairment and dementia, and is supported by The Gray Centre for Mobility and Activity at St. Joseph’s.

Lawson Health Research Institute is one of Canada’s top hospital-based research institutes, tackling the most pressing challenges in health care. As the research institute of London Health Sciences Centre and St. Joseph’s Health Care London, our innovation happens where care is delivered. Lawson research teams are at the leading-edge of science with the goal of improving health and the delivery of care for patients. Working in partnership with Western University, our researchers are encouraged to pursue their curiosity, collaborate often and share their discoveries widely. Research conducted through Lawson makes a difference in the lives of patients, families and communities around the world. To learn more, visit www.lawsonresearch.ca.

Communications Consultant & External Relations

Lawson Health Research Institute

T: 519-685-8500 ext. ext. 64059

C: 226-919-4748

@email

Study aiming to slow cognitive decline in older adults gets $1.5M

Led by Dr. Manuel Montero-Odasso and his team at Lawson Health Research Institute, the first large-scale Canadian clinical trial using personalized lifestyle intervention delivered at home to help older adults with mild cognitive impairment is getting underway with support from a Weston Foundation grant of $1.5 million.

Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is an intermediate stage between the expected cognitive decline of normal aging and the more serious decline of dementia. There is growing evidence that enhancing physical activity, stimulating cognitive training and addressing cardiovascular factors could delay or prevent the decline to dementia.

Part of the Canadian Consortium on Neurodegeneration in Aging (CCNA), the SYNERGIC-2 trial will provide virtual at-home interventions to 550 study participants with MCI, including personalized one-on-one coaching, to help make lifestyle and behavioural changes. This trial builds upon the successful SYNERGIC-1 trial, which used face-to-face interventions, by delivering them remotely using digital technology.

These interventions will target five areas including physical exercise, cognitive training, diet recommendations, sleep interventions and vascular risk factor management, with the goal of enhancing health and maintaining independence for individuals at risk for developing dementia.

“There are important risk factors related to exercise, diet, sleep and socialization,” says Dr. Montero-Odasso, Lawson Scientist, Geriatrician at St. Joseph’s Health Care London’s Parkwood Institute and a Professor at Western University. “If we can make the brain a little healthier with multiple lifestyle interventions, we may be able to delay or even prevent dementia.”

The year-long study includes 35 researchers recruiting a diverse population of older adults with MCI across 10 Canadian cities. The research teams are currently looking for participants ages 60-85 with MCI and additional dementia risk factors.

Researchers have created a digital platform to deliver the interventions at home with effective coaching strategies that will help to overcome barriers to lifestyle interventions, like difficulty accessing intervention sites, lack of time to attend gym sessions or living in rural/remote areas.

“There are many Canadians who are at high risk of developing dementia, based on their family history and genetics,” explains Dr. Howard Chertkow, Chair of Cognitive Neurology and Innovation at Baycrest Health Sciences, Scientific Director at CCNA and a co-investigator on the study. “Other risk factors include having high blood pressure and diabetes. We have seen that we can reduce the risk of getting dementia if we can get people to improve their lifestyles in multiple ways.”

Those interested in taking part in the study can contact @email for additional details.

The study is part of a global initiative known as World-Wide FINGERS, an interdisciplinary network working on the prevention of cognitive impairment and dementia, and is supported by The Gray Centre for Mobility and Activity at St. Joseph’s.

Study finds children in marginalized communities more likely to experience cardiac arrests

A new study shows children living in marginalized communities are at a higher risk of experiencing paediatric out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (POHCA) – a rare, life-threatening event occurring outside a hospital setting in which a child’s heart suddenly stops beating. It is estimated in other studies that the survival rate for POHCA is less than 10 per cent, and one-third of the children who survive POHCA will develop a significant neurological condition.

A province-wide case-control study from Western University, Lawson Health Research Institute and the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES) addressed a gap in current literature related to how social determinants of health impact the risk of POHCA. The study was published in the Journal of the American Heart Association.

“We know the outcomes for children who experience POHCA are really poor. Most don’t survive, and those who do often develop new and severe neurological impairments,” said lead author Samina Idrees, an epidemiology and biostatistics Masters graduate, who completed the work while studying at Western. “Given the significance of this health outcome and its potential preventability, we wanted to investigate further and shed light on any potential disparities.”

The study established that the odds of POHCA were higher for children living in areas with the highest levels of material deprivation – which incorporates average income, education, the proportion of lone parent families and housing quality. The likelihood of experiencing POHCA was also greater for those living in urban centres in Northern Ontario (relative to those in urban centres in Southern Ontario) with a population greater than 10,000, rural areas in Southern Ontario, and in areas with highest levels of unpaid professions, unemployment or non-working age individuals, high levels of instability and lower levels of ethnic diversity.

“Racialized communities sometimes have higher risks for certain health conditions,” said Idrees, in reference to the finding that children living in areas with the lowest levels of ethnic diversity had a higher risk of POHCA. “However, these findings are in line with the finding that immigrants have a lower risk of experiencing POHCA relative to those born in the country, likely due to the healthy immigrant effect, where immigrants arriving in Canada are usually in good health.”

Most cases of POHCA are caused by respiratory failure, and cardiac arrests in children can be attributed to a wide range of preventable and unpreventable factors, including drowning, sudden infant death syndrome, accidental ingestion or existing medical conditions.

Dr. Janice Tijssen, senior author on the study, Associate Scientist at Lawson, Professor at Western and Adjunct Scientist at ICES, noted that while there is a variety of factors that may contribute to out-of-hospital cardiac arrests in children, a common theme was that kids living in these marginalized communities are at higher risk of experiencing cardiac arrest.

The case study group included 1,826 children, aged one day to 17 years, who were transported to an emergency department in Ontario after they suffered an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest between April 1, 2004 and March 31, 2020. The case study group was matched to a control group on a one-to-four ratio and researchers identified cases of POHCA using the National Ambulatory Care Reporting System – which contains data for hospital-based and community-based ambulatory care.

Solutions to reduce rates of POHCA in marginalized communities

The researchers emphasized that these findings underscore the need to address disparities through targeted prevention and intervention efforts to reduce the odds of POHCA. These include finding opportunities to increase public health education and awareness around POHCA, as well as implementing measures related to social determinants of health such as improving access to health care, health literacy and preventative healthcare.

The study also suggests other ways for communities to help reduce incidents of POHCA, such as improving emergency medical services, providing education to equip more people with cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) skills and improving access to automated external defibrillators (AED).

“Information on how to provide CPR or how to apply an AED is very simple and anyone can learn,” said Tijssen, Associate Professor in the Departments of Paediatrics and Epidemiology & Biostatistics at the Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry and Medical Director of the Paediatric Critical Care Unit at Children's Hospital at London Health Sciences Centre. “Children as young as six or eight can learn how to respond to a cardiac arrest so it’s crucial to get out to these communities with this information.”

The team also included Western researchers Kelly Anderson and Yun-Hee Choi.

Study to examine health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic for mothers and their new babies

LONDON, ON - The COVID-19 pandemic has drastically altered many people’s lifestyles. Parents may be working from home, providing additional childcare or experiencing social isolation. Some are dealing with decreased work hours and loss of employment. With all these factors at hand, a team of researchers from Lawson Health Research Institute and Western University are investigating the possible health impacts on mothers and their babies who were born or will be born during the pandemic.

“This has been a stressful and pivotal time for everyone in the world, but we know the post-partum experience can greatly affect both the birthing person and their baby, in the short and long term,” says Dr. Genevieve Eastabrook, Associate Scientist at Lawson and Assistant Professor at Western’s Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry. “We know perceived stress in the perinatal period may have a contribution to health later in life for the birthing person and their children in terms of overall cardiovascular and metabolic health, bonding experiences, and risk of mood disorders.” Dr. Eastabrook is also an obstetrician-gynecologist (OB-GYN) at London Health Sciences Centre (LHSC).

As part of the new study, the London research team is using an approach called ‘One Health’ which offers a holistic perspective to explore how various risk factors and social determinants of health interact to affect health. This is being studied through the Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine at Western. “It’s important for us to think of the environment as all of our surroundings, including the things around us like health care, grocery stores, education and employment,” says Mei Yuan, MSc research student at Schulich Medicine & Dentistry. “The purpose of this study is to look at the pandemic response rather than the pandemic itself. We know that even if women haven’t been infected with COVID-19, it doesn’t mean they haven’t been impacted.”

Study participants are asked to complete a 30-minute questionnaire at around 6-12 weeks after their delivery. The questionnaire focuses on perceived stress, postpartum depressive symptoms, perceived social support, the impact of COVID-19, health-care access and breastfeeding. Data from the questionnaire will be linked with participants’ medical records to look for associations between the various factors and pregnancy outcomes. “Even though the study is mainly focused on maternal health, studies have shown that once mental health is affected it really does impact the infant’s health, especially in the area of attachment between baby and caregivers,” explains Yuan.

Data from the study will be compared to the Maternity Experiences Survey, a national survey of Canadian women compiled in 2007 which looked at experience, perception, knowledge and practice during pregnancy, birth and the early months of parenthood. “The unique aspect here is that we have a comparative group using a historic cohort to see whether or not there are differences in markers that increase risk of depression, perceived stress and lack of social support,” adds Dr. Eastabrook. “We will also look at some unique things from the pandemic, such as how the use of virtual care for antenatal, postpartum and baby care impacted people’s experiences.”

The research team hopes to recruit 300 mothers for this study who have given birth at LHSC, specifically during the pandemic. Interested participants can email the Pregnancy Research Group at @email. Once all the data is collected the goal will be to use the findings to improve post-partum care for mothers and their babies within this population group.

-30-

Lawson Health Research Institute is one of Canada’s top hospital-based research institutes, tackling the most pressing challenges in health care. As the research institute of London Health Sciences Centre and St. Joseph’s Health Care London, our innovation happens where care is delivered. Lawson research teams are at the leading-edge of science with the goal of improving health and the delivery of care for patients. Working in partnership with Western University, our researchers are encouraged to pursue their curiosity, collaborate often and share their discoveries widely. Research conducted through Lawson makes a difference in the lives of patients, families and communities around the world. To learn more, visit www.lawsonresearch.ca.

Western delivers an academic experience second to none. Since 1878, The Western Experience has combined academic excellence with life-long opportunities for intellectual, social and cultural growth in order to better serve our communities. Our research excellence expands knowledge and drives discovery with real-world application. Western attracts individuals with a broad worldview, seeking to study, influence and lead in the international community.

The Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry at Western University is one of Canada’s preeminent medical and dental schools. Established in 1881, it was one of the founding schools of Western University and is known for being the birthplace of family medicine in Canada. For more than 130 years, the School has demonstrated a commitment to academic excellence and a passion for scientific discovery.

Senior Media Relations Consultant

Communications & Public Engagement

T: 519-685-8500 ext. 73502

Celine.zadorsky@lhsc.on.ca

Study will use 3D bio-artificial tissue model to improve understanding of wound healing after glaucoma surgery

James Armstrong, an MD/PhD student at Western University’s Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry conducting research at Lawson Health Research Institute, is creating a 3D bio-artificial tissue model to study wound healing following glaucoma surgery.

There are currently no curative treatments for glaucoma, the leading cause of irreversible blindness world-wide. The only therapy that can delay the progression of the disease is the reduction of intra-ocular pressure, which can be accomplished by taking drugs or undergoing surgery. Surgery is usually a last resort if pharmacological treatment is unsuccessful as many of these surgeries fail due to excessive healing of the surgical wound. A dense, scar-like tissue can develop at the surgical site, which blocks the pressure-lowering effect and leads to surgical failure, revision and even blindness.

Armstrong will identify risk factors for fibrotic glaucoma surgery failure through reviews of electronic patient records and literature. Using the constructed model of the ocular tissue involved in glaucoma surgery, he will simulate the surgical wound to study the physiology of how the tissue heals and test potential drugs designed to modulate the wound healing process.

The project has been awarded a Lawson Internal Research Fund (IRF) Studentship, and is supervised by Lawson scientist and St. Joseph’s Health Care London physician Dr. Cindy Hutnik.

“Right now there is a shift happening towards earlier surgical interventions for glaucoma so an understanding of the wound healing response is critical to ensure safe and successful outcomes for patients,” Armstrong says. “Future work in this area could include developing a diagnostic test to inform physicians of a patients’ likelihood of excessive healing before the patient even sets foot in the operating room. This will allow surgeons to ‘customize’ how they pre-treat each individual patient with wound healing modulating drugs.”

Although this study is focused on wound healing within the eye, the same processes are at work in many other diseases. Understanding and having the ability to manipulate wound healing mechanisms could have widespread applicability, not only for glaucoma, but also for other diseases such as atherosclerosis, interstitial pulmonary fibrosis, hepatic fibrosis, systemic sclerosis or muscular dystrophy, as well as heart, kidney or liver failure.

“The IRF has given me the opportunity to pursue research in an area where any progress could impact a significant portion of the population,” Armstrong says. “It’s a great way for researchers who are early in their career to get a foot in the door. It allows them to collect the amount of data necessary to receive funding from larger granting agencies.”

The IRF is designed to provide Lawson scientists and students the opportunity to obtain start-up funds for new projects with the potential to obtain larger funding, be published in a high-impact journal, or provide a clinical benefit to patients. Funding is provided by the clinical departments of London Health Sciences Centre and St. Joseph’s Health Care London, as well as the hospital foundations (London Health Sciences Foundation and St. Joseph's Health Care Foundation).

Symposium features research on health through food and microbes

The past decade has featured rapid acceleration in the study of microbes and how they influence human and planetary health. This includes the study of probiotics and their diverse benefits.

On Friday, May 4, Lawson Health Research Institute (Lawson) and Western University hosted a free public symposium on health through food and microbes.

With more than 80 attendees, the symposium covered dynamic areas of research that are collectively impacting society and human wellbeing. These include the critical role of honey bees in pollination, bioremediation of toxic compounds, fermented food, maternal and infant nutrition and how microbes can confer a range of health benefits. The topics included a view of life in developing countries and efforts to help people overcome many challenges.

The event was opened by Dr. Bing Gan, Lawson scientist, plastic surgeon at St. Joseph's Health Care London and professor at Western’s Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry, who described his harrowing experience working for Doctors Without Borders in the Congo.

“We live in a microbial world, and beneficial ones are essential to the future of our planet and for human wellness and longevity,” says Dr. Gregor Reid, a scientist at Lawson, professor at Western’s Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry and lead organizer of this symposium. “The highly respected speakers at this event highlighted the potential for microbes to improve global health, and reminded us of the fragility of life on this planet.”

The event was made possible by a grant from the Gairdner Foundation for a lecture titled, “Food for 9.7 billion people,” by Dr. Rob Vos, Director Markets, Trade and Institutions, International Food Policy Research Institute, Washington, DC. The lecture was delivered by Dr. Reid as Dr. Vos unfortunately experienced travel delays.

The event also featured locally produced fermented foods provided by Booch and Nuts For Cheese.

Synthetic surfactant could ease breathing for patients with lung disease and injury

Human lungs are coated with a substance called surfactant which allows us to breathe easily. When lung surfactant is missing or depleted, which can happen with premature birth or lung injury, breathing becomes difficult. In a collaborative study between Lawson Health Research Institute and Stanford University, scientists have developed and tested a new synthetic surfactant that could lead to improved treatments for lung disease and injury.

Lung surfactant is made up of lipids and proteins which help lower tension on the lung’s surface, reducing the amount of effort needed to take a breath. The proteins, called surfactant-associated proteins, are very difficult to create in a laboratory and so the surfactant most commonly used in medicine is obtained from animal lungs.

London, Ontario has a rich legacy in surfactant research and innovation. Dr. Fred Possmayer, a scientist at Lawson and Western University, pioneered the technique used to purify and sterilize lung surfactant extracted from cows. Called bovine lipid extract surfactant (BLES), the therapeutic is made in London, Ontario and used by nearly all neonatal intensive care units in Canada to treat premature babies with respiratory distress.

“When we look at treating adults, surfactant therapy is more difficult. For example, their lungs are 20 times bigger than those of babies and so we need much higher doses of surfactant,” explains Dr. Ruud Veldhuizen, a scientist at Lawson and an associate professor at Western University’s Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry. “We therefore need to find novel approaches to surfactant therapy for adult patients.”

In this collaborative study, the research team took a new approach to creating synthetic surfactant. Rather than trying to recreate surfactant-associated proteins in the lab, scientists at Stanford created protein mimics. Pioneered by Dr. Annelise Barron, associate professor at Stanford, these protein mimics look like surfactant-associated proteins and have similar properties but are easier to create and more stable. As a result, the team was able to create a new synthetic surfactant.

Collaborating with the Stanford team, Dr. Veldhuizen evaluated the synthetic surfactant in animal models in his research lab at St. Joseph’s Health Care London. The study showed that, unlike other synthetic surfactants currently on the market, the new surfactant equaled or outperformed the animal-derived surfactant in every outcome. This included outperforming animal-derived surfactant in oxygenating blood, which is the lungs’ main purpose.

“The unique ability of the Veldhuizen lab to perform these rigorous and sophisticated studies was a critical aspect of the success of this project,” says Dr. Barron.

“These are very promising results,” says Dr. Veldhuizen. “For the first time, a synthetic surfactant has been developed which appears to be just as effective, if not more so, as that taken from the lungs of animals.”

The team estimates that the synthetic surfactant could be produced at as low as one quarter of the cost of the animal-derived surfactant. With a lower cost the synthetic surfactant could be tested with more lung diseases and injuries in adults and made available in more developing countries.

The team hopes to continue their research with further testing of the synthetic surfactant, including its long term effects. The team also hopes to test its ability to be customized for specific diseases. “Since it is made in the lab, we could combine the surfactant with other drugs like antibacterial agents and deliver it to specific areas of the lung, such as those where an infection is located,” explains Dr. Veldhuizen.

One disease the scientists would like to further study is acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). ARDS is characterized by a low amount of oxygen in the blood due to difficulty breathing. While current surfactants have been tested with ARDS patients, they have not been effective. Dr. Veldhuizen wants to combine this new synthetic surfactant with anti-inflammatory agents and antibacterial agents to test whether patient outcomes are improved.

The study, “Effective in vivo treatment of acute lung injury with helical, amphipathic peptoid mimics of pulmonary surfactant proteins,” is published in Scientific Reports.

Team players: FMT and microbiome research could have widespread impact

There is still much to learn about the human microbiome and its role in fighting disease, but ongoing studies at Lawson Health Research Institute, including a focus on fecal microbial transplants (FMT), are making strides in harnessing this complex system.

FMT is being studied in connection with conditions as varied as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, rheumatoid arthritis, atherosclerosis, HIV, cancer and multiple sclerosis.

FMT is already in clinical use for the treatment of C. diff (Clostridium difficile), and in addition to showing promise in the treatment of other diseases, it is also being studied as a way to improve response to existing cancer treatments and ease treatment side effects.

Dr. Saman Maleki, a Scientist at Lawson Health Research Institute and the London Regional Cancer Program (LRCP) at London Health Sciences Centre (LHSC), says they’ve just begun to explore the possibilities.

"We are just starting to study FMT as an intervention outside its traditional use in patients with C. difficile infection, and we will be expanding to other areas, particularly in cancer.”

FMT can overhaul a patient’s microbiome, Dr. Maleki explains, and a healthy microbiome is beneficial especially when a treatment is trying to activate the body’s immune system.

Dr. Michael Silverman, Lawson Associate Scientist and Medical Director of St. Joseph’s Health Care London’s Infectious Diseases Care Program, is a pioneer in the field of FMT. He has been performing the procedure since 2003 with C. difficile patients and was one of the first in North America to do so. He sees a wide range of possible applications.

“FMT has enormous potential in being an important adjunctive therapy in many cancers. It may, for example, help cancer patients respond to immunotherapy,” says Dr. Silverman, who is also Chair/Chief of Infectious Disease at St. Joseph’s Health Care London, LHSC and Western University. “The potential to impact autoimmune and metabolic diseases is also quite exciting, but still in early development.”

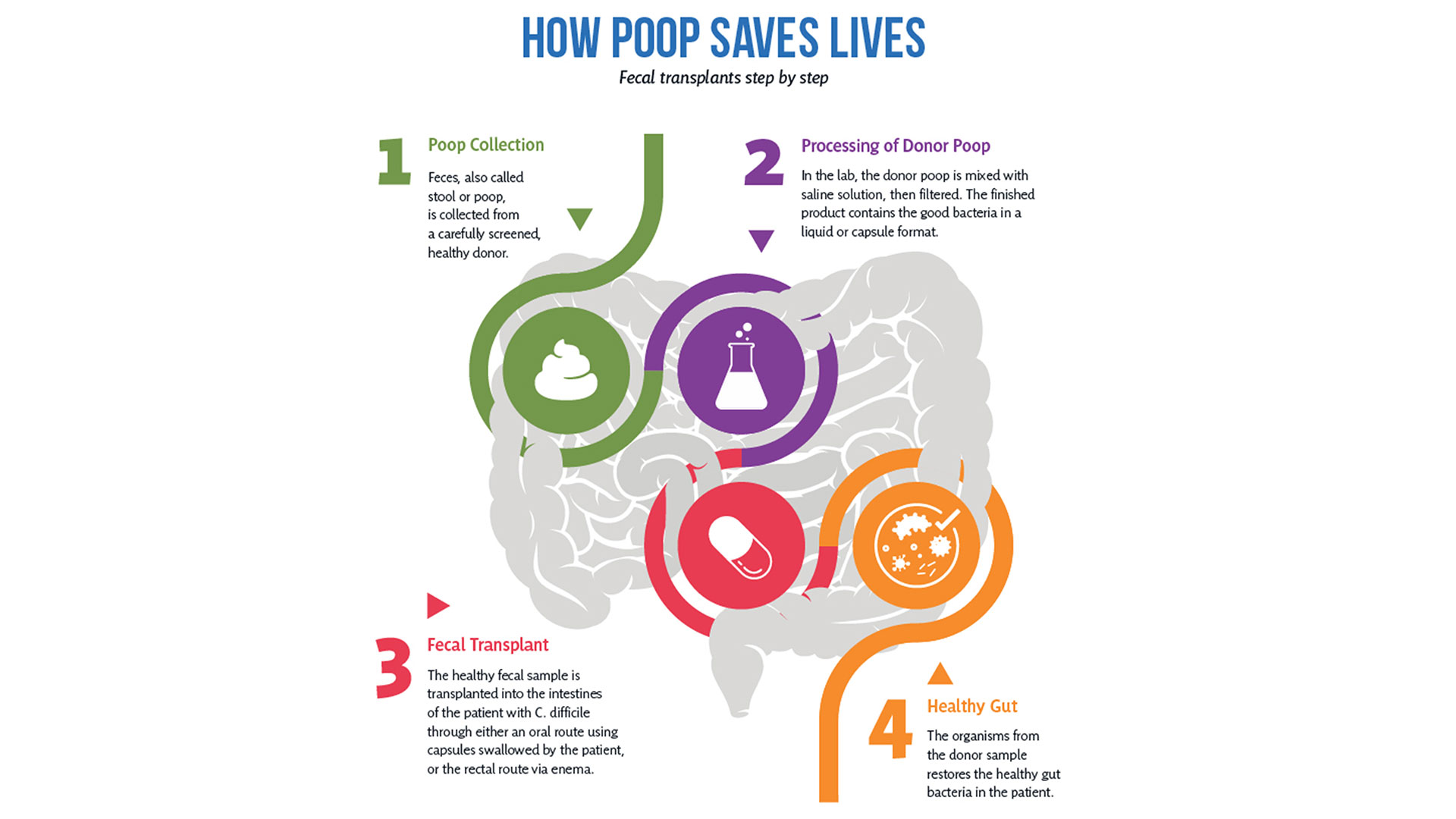

So how does it work?

After rigorous screening, stool from a healthy donor is collected and then processed in a lab into a liquid or capsule containing the good bacteria, which can then be administered to a patient’s gastrointestinal tract.

The Lawson team is also one of few delivering FMT using specially-prepared oral capsules. Introduced in 2018, they have been a game changer in patient acceptance and ease of administration, according to Research Coordinator Dr. SeemaNair Parvathy, who has been coordinating the program since 2015.

“There is a link between the fitness of the intestinal microbiome and the fitness of the immune system,” says Dr. John Lenehan, Associate Scientist at Lawson and Medical Oncologist at LHSC. “A ‘healthy’ microbiome leads to a more robust immune response when using immunotherapy. FMT from a healthy donor is expected to improve the fitness of the recipient’s intestinal microbiome and promote a better immune response.”

People with chronic disease can often experience what’s called a ‘leaky gut,’ allowing food, bacterial and microbial components to pass through the intestinal wall, negatively impacting the immune system.

“When people get FMTs their intestinal permeability improves – meaning it actually reduces,” says Dr. Jeremy Burton, Lawson Scientist and Research Chair of Human Microbiome and Probiotics at Lawson and St. Joseph’s. “What changes that intestinal permeability? The microbes at the site. They play a role in interacting with the host cells, providing nutrients and vitamins.”

With the immune system so closely tied to the health of the microbiome, it’s not surprising scientists are exploring how strengthening one can have a big impact on the other.

Boosting immunotherapy

Immunotherapy can be used to either stimulate or suppress the immune system to help the body fight disease, and FMT is showing promise in reducing resistance to the treatment.

While immunotherapy has been effective in treating a number of cancers – the number one cause of death in Canada – not all patients respond to the treatment.

But early work presented at a conference by the Lawson team for the Journal for ImmunoTherapy of Cancer has shown that using FMT to modify the microbiome could reduce resistance to immunotherapy. The study involved patients from LHSC with advanced melanoma, a type of skin cancer.

While in the very early stages, the combination of FMT and anti-PD1 immunotherapy has been found to be safe, and it appears that FMT could make tumours more responsive to the immunotherapy treatment.

“Microbiome-based treatment strategies, including FMT, have a high potential in oncology,” says Dr. Maleki. “Our team is also exploring its potential in treating pancreatic cancer.”

The research is so interesting that a recent Nature article listed the Phase I melanoma trial as “seminal” research. The study was also unique in that it used healthy donors, as opposed to donors who had previously responded to immunotherapy treatment.

A separate Lawson study with LHSC patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma, a type of kidney cancer, published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology, also looked at combining immunotherapy and FMT to ease the adverse effects of the treatment.

The Phase I study, led by Dr. Maleki and Dr. Ricardo Fernandes, Medical Oncologist at LHSC, found adding FMT to doublet immunotherapy was safe, but further study is needed to determine whether it could bring about changes in the microbiome and immune system.

Dr. Lenehan says Lawson researchers are in a position to be leaders in this field in the near future for two reasons.

“One is that other academic researchers have not been able to assemble the expertise, and some who have, do not have the access to healthy donor stool. The second is that some biotechnology companies are interested in FMT, but almost exclusively for C. difficile infections.”

Autoimmune, metabolic and other illnesses

Two other areas that have seen recent advances include FMT for the treatment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and multiple sclerosis.

“The gut microbiome is very important in the metabolism of foods and metabolic products. It can therefore have a major effect on obesity and atherosclerosis,” says Dr. Silverman. “It also is tightly involved in regulating the immune system and therefore moderating the microbiome may potentially impact autoimmune diseases.”

A study published in 2020 by the team in The American Journal of Gastroenterology showed that FMT appears to reduce intestinal permeability in patients with NAFLD.

The number of people with NAFLD is growing rapidly and studies show patients have different microbiota than healthy persons.

The trial included 21 NAFLD patients from LHSC and St. Joseph’s. While the researchers found no changes in percentage of liver fat or insulin resistance, they observed significant reduction in intestinal permeability in those patients who had elevated intestinal permeability at the study’s start (seven patients in total). They also observed changes to the gut microbiome in all patients who received a fecal transplant from a healthy donor.

“Metabolic syndromes including obesity and its complications of NAFLD and atherosclerosis are massive public health problems. Any impact on these would be of huge importance,” Dr. Silverman adds. “Autoimmune diseases also cause major morbidity and mortality. We have a lot of work to do before we can consider FMT as a routine therapy for any of these conditions, but the long-term promise is great.”

Research into the use of FMT for treatment of patients with multiple sclerosis is in the very early stages. But patients with MS show a difference in gut microbiota and higher small intestine permeability, which could contribute to the development of the disease.

A Phase I trial by the Lawson team published in the Multiple Sclerosis Journal – Experimental, Translational and Clinical, found FMT to be safe and tolerable.

While the study was very small, MS patients treated with FMT were found to have beneficial changes to gut microbiota and intestinal permeability, but further study is needed to determine if FMT could be used as a treatment.

Lawson scientists are also currently studying the use of FMT for patients with atherosclerosis, along with ongoing studies on melanoma and lung cancer. Funding for a study on pancreatic cancer has been secured and researchers are in the process of planning trials for a number of other applications.

Dr. Lenehan says, “The microbiome is connected to several diseases and their treatments. Evidence is growing that an individual’s health is related to their microbiome.”

The donor challenge

The challenge of finding fecal donors for FMT and the cost of that process remain an issue for research into this promising treatment, even as more potential applications are discovered.

There is currently no process in place to match donors and recipients – as with organ donation – but there is an extensive screening process for both infectious and non-infectious conditions, one that needs to be repeated if a donor experiences any lifestyle changes.

Dr. Burton says, “We still don't understand the full role of the microbiota. We have to ensure that we're not giving patients a microbiota that might cause them some other issue in the future, so the donors are screened very thoroughly for that.”

Screening also excludes donors with an increased risk of developing the diseases scientists are hoping to treat, such as metabolic syndrome related conditions.

A 2017 article published in Open Forum Infectious Diseases by Drs. Silverman and Burton found the cost of screening high numbers of potential donors could make establishing local programs extremely difficult, so having a central program such as the one in London could help patients in many regions.

In the study, only five of 46 potential donors passed the history, examination, blood, stool and urine tests, and of the five, four later travelled or had illnesses that made donation inadvisable.

The search continues in London for potential donors to help drive this research forward. You can read one donor’s story and learn how you can get involved here.

More on FMT and the microbiome:

Drugs vs. bugs: Harnessing the microbiome to improve treatments

Communications Consultant & External Relations

Lawson Health Research Institute

T: 519-685-8500 ext. ext. 64059

C: 226-919-4748

@email

The children of Masiphumelele Township

Written by Dr. Gregor Reid, scientist at Lawson and professor at the Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry, Western University

Just off the main road from Cape Town, South Africa to Simon’s Town, sits Masiphumelele Township where challenges of poverty, malnutrition, HIV and the risk of violence face people every day.

It is also the location for the Desmond Tutu HIV Foundation Youth Centre, a safe haven that provides adolescent-friendly sexual and reproductive health services alongside educational and recreational activities for youth living in Masiphumelele and surrounding areas.

To understand some of the dangers that children face, in 2017 about 270,000 people in South Africa were newly infected with HIV, adding to one of the highest HIV prevalence rates in the world. The Tutu Youth Centre aims at helping educate youth to reduce their risk of becoming another HIV statistic.

I was invited there by University of Cape Town Professor Jo-Ann Passmore, a woman not only recognized for her research but whose passion for helping others is reflected in her warm smile (fourth from left in the below group photo). She asked if I would be interested in holding a workshop to illustrate to the youth how using sachets of probiotic bacteria could empower them. I jumped at the chance. On an afternoon break from the Keystone Symposium, thirty researchers joined me along with Jo-Ann and my wife Debbie, a teacher of children with learning disabilities.

After a tour of the areas where children learn on computers, play games in safety, or have personal discussions about sexual health, everyone filled the room with a stunning backdrop of the Nobel Laureate’s image. Having been privileged to meet the Archbishop when he was hosted by St. Joseph’s Health Care Foundation in 2008, it was a nerve-tingling experience.

Giving a lecture on beneficial microbes is hard enough to peers sitting in the back of the room, but to do so with young South Africans was somewhat more daunting. However, it proved to be a lot of fun especially when we had to identify kids who were good leaders (the boys all pointed to a girl), at making stuff and selling it to others (two boys stood out). By the end, we had picked the staff of a new company.

The next step was for four groups to go and decide on the company’s name, what products they’d make from the probiotic sachets (the options were many from yoghurt to cereals, juices and maize), what marketing tools they would use and who they would target to obtain a respectable income.

Interestingly, several of the conference participants seemed less engaged, as if they had never considered how microbiology research could affect real lives. In front of them were children facing huge challenges on a day-to-day basis. In one group, the kids were quiet until my wife brought out pens and paper, then they went to town designing products, names and labels. A lesson for me on how different people need different stimuli to become engaged. The faculty left early to beat the traffic back to Cape Town, so unfortunately, they did not hear the outcome of the children’s work.

When we re-assembled to present the results, I was impressed with what could be created in such a short time. My favourite was the Amazing Maize, a bottle shaped like a corn cob. It emphasized the importance of marketing and for products to taste and look good to be purchased.

It had been over ten years since Archbishop Tutu had applauded us for the Western Heads East project, and thanked us for empowering women and youth and contributing to nutrition in Africa. Since then, thanks to the huge efforts of Western University staff and students, and more recently IDRC funding and partnerships especially with Yoba-for-life, Heifer International and Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology, over 260,000 people in east Africa are now consuming probiotic yoghurt every week. The children of the South African townships were maybe too young to join in this new wave of microenterprises, but at least now they have heard about it and the importance of fermented food and beneficial bacteria.

In the background of the workshop several wonderful women committed to start up a new production unit. I left them some sachets to try out the process.

But it was me who left with the biggest lesson on how precious each life is, and how those of us with the knowledge need to provide the means for others to use their own talents to fulfill the purpose that their lives surely have.

No better way than to start with the children.

Gregor Reid PhD MBA FCAHS FRSC

Scientist, Lawson Health Research Institute, and Professor, Western University

London, Canada

Time for Canada to reclaim its place as a leader in scientific discovery

The following editorial was provided to Post Media by Dr. David Hill, scientific director, Lawson Health Research Institute.

Last week the Nobel Prizes for 2017 were announced, recognizing incredible advances in science that will impact all our lives for the better. If you were looking for Canadian scientists amongst the teams, you would be disappointed.

According to a federal government report commissioned by the minister of science titled Investing in Canada’s Future — Strengthening the Foundations of Canadian Research and released in April, Canada’s momentum in the sciences has never been worse.

Our country’s investment in key emerging areas such as artificial intelligence, clean technology, nanotechnology, immunotherapy, bioinformatics or bio-engineering is flat-lined or declining, and falling seriously behind competitor nations.

We are not talking about matching the United States or Germany. Canada invests less in science research and development relative to gross domestic product than does Taiwan or Singapore.

Why should we care?

Because smart science delivers technologies we take for granted every day, such as Siri on our iPhones, minimally invasive surgery and secure online banking.

Science also creates companies, delivers high-paying and rewarding jobs, and is the backbone of the economy.

In London, Ont., jobs that depend on advancing science include those at Lawson Health Research Institute, the research institute of London Health Sciences Centre and St. Joseph’s Health Care London and where I work; academic institutions such as Western University and Fanshawe College; and local businesses generating health devices, computer software and engineered products. A lack of investment in science could be devastating to our city.

This report places the failure to invest in science at the door of successive federal governments during the past decade.

Of course, it is not only government that should invest in science. It is industry that takes proven scientific findings and translates them into products we all consume.

But these innovative products need to start somewhere, most often in the laboratory. Fostering high risk, fundamental discovery science should be a core responsibility of government in a knowledge-driven economy.

In Canada, the contribution of federal funds to discovery science is now below 25 per cent of the total research investment, and lower than most of our competitor nations. Consequently, research funds are scarce, laboratories are closing, fewer students are receiving advanced training, and fewer new businesses are emerging.

It is not too late.

The report provides evidence to show that Canadian scientists are still respected leaders in their fields. The engine simply needs fuel.

To return Canada’s discovery science enterprise back to 2006 productivity levels, we require an additional investment of $1.3 billion during four years, representing 0.1 per cent of the entire federal budget for each of those years.

The investment quickly pays for itself. Every $1 invested in fundamental research has been calculated to return $2.20 to $2.50 in direct and indirect economic activity.

Next year’s federal budget is being put together right now in Ottawa, and we have an opportunity to reclaim our past reputation as a discovery nation; a nation that brought the world insulin, the Canadarm, Pablum, canola and the electron microscope.

The journey toward that next Canadian Nobel Prize needs to start now.

Dr. David Hill

Scientific Director

Lawson Health Research Institute