Search

Search

Dementia doesn’t have to be your destiny

Tackling a “dirty dozen” list of health and lifestyle factors can go a long way in lowering the risk of dementia, say London experts.

Many people could greatly improve their odds against developing dementia by making four, low-cost lifestyle changes – today.

In the first study of its kind, researchers at Lawson Research Institute (Lawson) and Western University have found that about half of dementia cases in Canada can be influenced by 12 lifestyle factors.

Topping the “dirty dozen” list across Canadians’ lifespan, and especially notable from mid-life onwards, are physical inactivity, hearing loss, obesity and hypertension.

The solutions:

- Get off the couch and get moving

- Tackle hearing loss early

- Lose weight

- Get assessed and treated for high blood pressure

“While lifestyle changes aren’t a magic pill to prevent all dementias, they’re an empowering way to reduce the overall risk,” says Lawson researcher and study lead author, Surim Son, a Western University PhD candidate who with the dementia research program at St. Joseph’s Health Care London (St. Joseph’s).

“We’re talking about significant benefits to Canadian health and health systems,” adds Son.

The findings could also have profound implications in refocusing health policy priorities. The Public Health Agency of Canada is already highlighting the study as part of its resources for national health policy advisors, she notes.

This study is the first to weigh Canadians’ lifestyles and habits against 12 potentially modifiable risk factors for dementia, and the first globally to include sleep disruption on the list.

Son’s paper, published in The Journal of Prevention of Alzheimer’s Disease, builds on a 2017 study in the Lancet that shows 12 modifiable risk factors throughout the course of life could contribute to 40 per cent of dementias around the world.

But Canada’s numbers are considerably higher because more of us indulge in weightier lifestyle risks. For example, four of every five older Canadian adults don’t exercise regularly; one in three is obese or has hypertension; and one in five has hearing loss.

"If half of the dementia cases in Canada are linked to modifiable lifestyle risk factors, this suggests that, today, prevention may be the most effective form of treatment," says Dr. Manuel Montero-Odasso, co-author of the paper and Director of the Brain & Gait Lab at St. Joseph’s Parkwood Institute.

“Dementia doesn’t have to be your destiny, even if that’s part of your genetic story. Our results from the SYNERGIC Trial shows almost everyone can change their risk factors and improve their cognitive resilience,” says Montero-Odasso, who was recently awarded a $2.4-million Canadian Institutes of Health Research grant to train professionals in risk reduction and care for people living with cognitive impairment.

Montero-Odasso’s advice: “Go out for a walk and keep moving. Get a hearing assessment. Keep your blood pressure in check. It’s low-cost and easy to implement. It’s good for your body health, even beyond improving your brain health and reducing your dementia risk.”

The 12 potential modifiable factors (based on a study of 30,000 Canadians over the age of 45), weighted from most significant factor to least:

- Physical inactivity

- Hearing loss

- Obesity

- Hypertension

- Traumatic brain injury

- Depression

- Less education in early life

- Sleep disturbances

- Diabetes

- Smoking

- Excessive alcohol

- Social isolation

Dementia research hits the ‘mark’

St. Joseph’s Health Care London is at the forefront of national research exploring biomarkers to better predict dementia and slow its onset.

Dr. Michael Borrie is now seeing grandchildren of patients who came to his clinic when he first started Alzheimer’s research 30 years ago.

His message to this new generation is more hopeful than ever, bolstered by ever-more-reliable ways of early detection and being tantalizingly close to a future of predicting dementia and intervening even before symptoms appear.

“The ultimate goal is to slow cognitive decline – and to stop it if we can – so that people can live independently, and happier, for a lot longer,” says Borrie, Medical Director of the Aging Brain and Memory Clinic at St. Joseph’s Health Care London (St. Joseph’s).

“We’re aiming to alter the trajectory of dementia,” he says.

A geriatrician, clinician and researcher, Borrie is also Platform Lead for the Comprehensive Assessment of Neurodegeneration and Dementia (COMPASS-ND), a long-term study within the Canadian Consortium on Neurodegeneration and Aging (CCNA).

Recently, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research announced $20.6 million in funding to continue the work of CCNA, a 30-site, multi-pronged project of which the St. Joseph’s-based team is the lead player. The grant will enable them to advance the frontiers of dementia research to benefit real-world patients here and across the country.

Solving mysteries with biomarkers

Despite the prevalence of Alzheimer’s and other neurodegenerative diseases – and with more than 10,000 new diagnoses in Canada each year – there are still many mysteries to solve: Why do some people have early-onset dementia while others, super-agers, remain alert and active in their 90s? What’s happening genetically, in their environment and personal medical history to advance or protect against the disease?

What is known, however, is the link between damaged nerve cells and specific proteins that misfold and clump together to form amyloid plaques and tau tangles in the brain. Detecting these abnormal proteins early is an important key to diagnosis and prediction.

Locally, the most comprehensive tool has been state-of-the-art brain Positron Emission Tomography (PET) scanning at St. Joseph’s Imaging. Lawson researchers are also involved in reliably detecting amyloid proteins by analyzing participants’ cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) – a surprisingly accurate way of confirming imaging results, says geriatrician Dr. Jaspreet Bhangu, a Lawson scientist and head of the biomarker project.

Through the BioMIND regional research project, Lawson scientists are analyzing PET scans, blood and CSF samples to check for specific protein biomarkers. If shown to be reliable, a series of these tests over time could signal whether the disease is progressing, and could predict whether it will progress or respond to treatment.

All that gets added to an arsenal that includes tests of behaviour, memory and cognitive function.

“It’s a triple assessment, or even a quadruple one, that we can conduct over time. We hope to use these advanced tests to provide vital information, similar to what is done in certain types of cancer,” Bhangu says.

But that’s not all.

Testing potential treatments

St. Joseph’s is also one of the country’s most active sites for clinical trials into whether novel medications might be able to directly pinpoint and destroy the proteins that cause Alzheimer disease.

“This is the intersection of cutting-edge research, top-notch resources and excellent clinical practice to develop personalized treatments,” says Bhangu. “What makes us unique in Canada among dementia researchers is that our science is taking us from bench to bedside – a rapid turnaround from research to direct patient benefit.”

If a person has a strong family history of Alzheimer disease and no symptoms – but does have positive biomarkers confirming presence of disease – they may then choose to take part in a randomized controlled trial to try to alter the trajectory of the disease.

“It’s still in a research context, still in clinical trials – but if Health Canada ultimately approves a treatment, we’ll have the ability and the patient database to be able to translate our findings into clinical practice much more quickly instead of waiting for years,” says Borrie.

All this is good news for a generation eager for answers, Borrie says.

“When we learn more about the mechanisms of the disease, we can find more effective, earlier treatments. And if we can treat people earlier, we hope to move the disease progression curve to the right, to add more years of good cognitive health to someone’s life.”

Detecting the Undetectable

A simple fall can lead to long-term hand problems such as arthritis due to fracturing the scaphoid bone in the wrist. Scaphoid fractures are known to have the highest rate of healing failures. While this bone’s fragile blood supply is commonly thought to be the main reason for why it is difficult to heal, Dr. Ruby Grewal is looking into a different reason – infection.

Infections are known to cause difficulty in healing bones, but traditional tests for infections in the scaphoid have come up negative. With new advancements in detecting microbial DNA, scientists can now test for ‘clinically undetectable’ infections.

In a new study, Dr. Grewal will use microbial DNA test whether or not there are infections in the scaphoid fracture which causes improper healing of the bone.

“The goal of this study is to use advanced DNA sequencing technology to test whether or not we can detect evidence of microorganisms in non-healing scaphoids,” explains Dr. Grewal, Lawson Scientist and Orthopaedic Surgeon at the Roth McFarlane Hand and Upper Limb Centre (HULC) at St. Joseph’s Health Care London.

Finding new causes of improper healing of the scaphoid bone could improve treatments for individuals with these injuries and prevent long-term problems with hand function. These insights into the causes of improper healing could also prevent young patients from developing wrist arthritis.

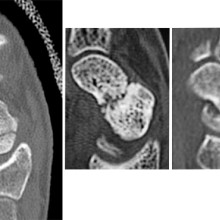

From left to right: Normal scaphoid fracture. Scaphoid fracture that is struggling to heal. Scaphoid non-union where the bone has failed to heal.

Dr. Grewal’s study is being funded through the Lawson Internal Research Fund (IRF).

“The financial support provided by Lawson’s IRF is of utmost importance to researchers. These funds will allow our team to embark on a new area of research and test a novel hypothesis,” says Dr. Grewal, “While traditional granting agencies are reluctant to fund completely novel areas of research without pilot data to prove feasibility, the Lawson IRF allows researchers to investigate new theories in a sound scientific manner. Without the ability to test new ideas we cannot innovate and make advancements in health care. Support for this project allows for that.”

Lawson’s IRF is designed to provide Lawson scientists the opportunity to obtain start-up funds for new projects with the potential to obtain larger funding, be published in a high-impact journal, or provide a clinical benefit to patients. Funding is provided by the clinical departments of London Health Sciences Centre and St. Joseph’s Health Care London, as well as the hospital foundations (London Health Sciences Foundation and St. Joseph’s Health Care Foundation).