Search

Search

Diagnosing COVID-19 using artificial intelligence

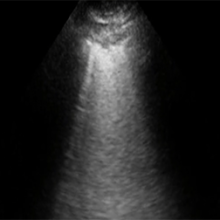

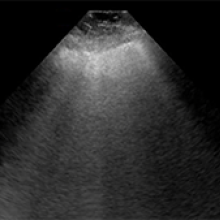

LONDON, ON – A team of researchers at Lawson Health Research Institute is investigating whether an artificial neural network could be used to diagnose COVID-19. The AI system is being trained to learn and recognize patterns in ultrasound lung scans of patients with confirmed COVID-19 at London Health Sciences Centre (LHSC) by comparing them to ultrasound scans of patients with other types of lung infections.

“Machines are able to find patterns that humans cannot see or even imagine. Lung ultrasound scans of patients with COVID-19 pneumonia produce a highly abnormal imaging pattern. This pattern isn’t unique to COVID-19, and can be seen in other causes of pneumonia. It is plausible, however, that there are details that distinguish COVID-19 at the pixel level that cannot be perceived by the human eye,” explains Dr. Robert Arntfield, Lawson Researcher and Medical Director of the Critical Care Trauma Centre at LHSC. “If we can train a neural network to learn and identify these unique characteristics among different scans, we can apply this AI to enhance the diagnostic power of portable ultrasound.”

Point-of-care ultrasound has become increasingly important for the care of critically ill patients and LHSC is a global leader in the use of this technology at the bedside. Lung ultrasound has proven to be effective in diagnosing different types of lung infections and illnesses, such as pneumonia, with a high degree of accuracy. The convenience, portability and low cost of using these machines has helped them become a standard bedside tool in emergency departments and intensive care units worldwide.

This research project is part of a grassroots effort by a small group of local clinicians to innovate and create technology to solve sophisticated problems with AI. With many of Dr. Arntfield’s team having a background in computer programming, they were able to code the neural network being tested. Minimal funding was required, with the project being driven largely by the urgency of COVID-19 coinciding with the recent creation of this clinical AI working group.

“Our research team has used AI to help improve diagnostics related to other parts of the body. This project is a great example of the unique ability we have here in London to be agile: that is, to identify a gap and move quickly towards finding a solution,” says Dr. Arntfield. “I am thrilled that we were able to move through the approval process quickly, and get our ideas working in such a short amount of time.”

-30-

Downloadable Media

Dr. Robert Arntfield

COVID-19 pneumonia ultrasound

NON COVID-19 pneumonia ultrasound

Lawson Health Research Institute is one of Canada’s top hospital-based research institutes, tackling the most pressing challenges in health care. As the research institute of London Health Sciences Centre and St. Joseph’s Health Care London, our innovation happens where care is delivered. Lawson research teams are at the leading-edge of science with the goal of improving health and the delivery of care for patients. Working in partnership with Western University, our researchers are encouraged to pursue their curiosity, collaborate often and share their discoveries widely. Research conducted through Lawson makes a difference in the lives of patients, families and communities around the world. To learn more, visit www.lawsonresearch.ca.

Senior Media Relations Consultant

Communications & Public Engagement

T: 519-685-8500 ext. 73502

Celine.zadorsky@lhsc.on.ca

Differences in walking patterns could predict type of cognitive decline in older adults

LONDON, ON - Canadian researchers are the first to study how different patterns in the way older adults walk could more accurately diagnose different types of dementia and identify Alzheimer’s disease.

A new study by a Canadian research team, led by London researchers from Lawson Health Research Institute and Western University, evaluated the walking patterns and brain function of 500 participants currently enrolled in clinical trials. Their findings are published today in Alzheimer's & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer's Association.

“We have longstanding evidence showing that cognitive problems, such as poor memory and executive dysfunction, can be predictors of dementia. Now, we’re seeing that motor performance, specifically the way you walk, can help diagnose different types of neurodegenerative conditions,” says Dr. Manuel Montero-Odasso, Scientist at Lawson and Professor at Western’s Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry.

Dr. Montero-Odasso is world renowned for his research on the relationship between mobility and cognitive decline in aging. Leading the Mobility, Exercise and Cognition (MEC) team in London, he is pioneering novel diagnostic approaches and treatments to prevent and combat early dementia.

This study compared gait impairments across the cognitive spectrum, including people with Subjective Cognitive Impairment, Parkinson’s Disease, Mild Cognitive Impairment, Alzheimer’s disease, Lewy body dementia and Frontotemporal dementia, as well as cognitively healthy controls.

Four independent gait patterns were identified: rhythm, pace, variability and postural control. Only high gait variability was associated with lower cognitive performance and it identified Alzheimer’s disease with 70 per cent accuracy. Gait variability means the stride-to-stride fluctuations in distance and timing that happen when we walk.

“This is the first strong evidence showing that gait variability is an important marker for processes happening in areas of the brain that are linked to both cognitive impairment and motor control,” notes Dr. Frederico Perruccini-Faria, Research Assistant at Lawson and Postdoctoral Associate at Western’s Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry, who is first author on the paper. “We’ve shown that high gait variability as a marker of this cognitive-cortical dysfunction can reliably identify Alzheimer’s disease compared to other neurodegenerative disorders.”

When cognitive-cortical dysfunction is happening, the person’s ability to perform multiple tasks at the same time is impacted, such as talking while walking or chopping vegetables while chatting with family.

Having gait variability as a motor marker for cognitive decline and different types of conditions could allow for gait assessment to be used as a clinical test, for example having patients use wearable technology. “We see gait variability being similar to an arrhythmia. Health care providers could measure it with patients in the clinic, similar to how we assess heart rhythm with electrocardiograms,” adds Dr. Montero-Odasso.

This study was primarily funded by the Canadian Consortium on Neurodegeneration in Aging (CCNA), a collaborative research program tackling the challenge of dementia and other neurodegenerative illnesses. The CCNA was supported by a grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research

-30-

Lawson Health Research Institute is one of Canada’s top hospital-based research institutes, tackling the most pressing challenges in health care. As the research institute of London Health Sciences Centre and St. Joseph’s Health Care London, our innovation happens where care is delivered. Lawson research teams are at the leading-edge of science with the goal of improving health and the delivery of care for patients. Working in partnership with Western University, our researchers are encouraged to pursue their curiosity, collaborate often and share their discoveries widely. Research conducted through Lawson makes a difference in the lives of patients, families and communities around the world. To learn more, visit www.lawsonresearch.ca.

Western delivers an academic experience second to none. Since 1878, The Western Experience has combined academic excellence with life-long opportunities for intellectual, social and cultural growth in order to better serve our communities. Our research excellence expands knowledge and drives discovery with real-world application. Western attracts individuals with a broad worldview, seeking to study, influence and lead in the international community.

The Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry at Western University is one of Canada’s preeminent medical and dental schools. Established in 1881, it was one of the founding schools of Western University and is known for being the birthplace of family medicine in Canada. For more than 130 years, the School has demonstrated a commitment to academic excellence and a passion for scientific discovery.

Senior Media Relations Consultant

Communications & Public Engagement

T: 519-685-8500 ext. 73502

Celine.zadorsky@lhsc.on.ca

Differences in walking patterns could predict type of cognitive decline in older adults

Canadian researchers are the first to study how patterns in the way older adults walk could more accurately diagnose different types of dementia and identify Alzheimer’s disease.

A new study by a Canadian research team, led by London researchers from Lawson Health Research Institute and Western University, evaluated the walking patterns and brain function of 500 participants currently enrolled in clinical trials. Their findings are published in Alzheimer's & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer's Association.

Dr. Montero-Odasso is world renowned for his research on the relationship between mobility and cognitive decline in aging. Leading the Mobility, Exercise and Cognition (MEC) team in London, he is pioneering novel diagnostic approaches and treatments to prevent and combat early dementia. Dr. Montero-Odasso is also co-lead of the Mobility, Exercise and Cognition Team at CCNA, a team composed of 22 researchers and 6 trainees.

This study compared gait impairments across the cognitive spectrum, including people with Subjective Cognitive Impairment, Parkinson’s Disease, Mild Cognitive Impairment, Alzheimer’s disease, Lewy body dementia and Frontotemporal dementia, as well as cognitively healthy controls. The study used data from the COMPASS-ND Cohort and the Gait and Brain Study Cohort.

Gait assessment looks at the way in which we move our whole body from one point to another, helping to analyze mobility and the brain processes involved.

Four independent gait patterns were identified: rhythm, pace, variability and postural control. Only high gait variability was associated with lower cognitive performance and it identified Alzheimer’s disease with 70 per cent accuracy. Gait variability means the stride-to-stride fluctuations in distance and timing that happen when we walk.

“This is the first strong evidence showing that gait variability is an important marker for processes happening in areas of the brain that are linked to both cognitive impairment and motor control,” notes Dr. Frederico Perruccini-Faria, Research Assistant at Lawson and Postdoctoral Associate at Western’s Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry, who is first author on the paper.

“We’ve shown that high gait variability as a marker of this cognitive-cortical dysfunction can reliably identify Alzheimer’s disease compared to other neurodegenerative disorders.”

When cognitive-cortical dysfunction is happening, the person’s ability to perform multiple tasks at the same time is impacted, such as talking while walking or chopping vegetables while chatting with family.

“Having gait variability as a motor marker for cognitive decline and different types of conditions could allow for gait assessment to be used as a clinical test, for example having patients use wearable technology,” says Dr. Richard Camicioli, Professor at the University of Alberta and co-senior author on the paper.

The London team collaborated with researchers at the University of Toronto, University of Calgary and University of Alberta. They are part of the Canadian Consortium on Neurodegeneration of Aging (CCNA), a collaborative research program tackling the challenge of dementia and other neurodegenerative illnesses.

Dr. Montero-Odasso adds that this gait variability could be perceived as similar to an arrhythmia. Health care providers could potentially measure it in clinical settings, like how heart rhythm is assessed with electrocardiograms.

This study was primarily funded by CCNA, supported by a grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

Discovery shows promise for treatment of glaucoma

In a new study from Lawson Health Research Institute (Lawson), scientists have discovered that a specific protein has the potential to be used to treat some patients with primary open-angle glaucoma.

Primary open-angle glaucoma is the most common type of glaucoma, which is a group of diseases that affect nearly 70 million people worldwide. Glaucoma is characterized by progressive damage to the optic nerve which ultimately leads to blindness. In this new study, led by Dr. Sunil Parapuram, researchers examined the role of a protein called “phosphatase and tensin homolog” (PTEN) in the trabecular meshwork. The trabecular meshwork is a porous tissue in the eye through which the clear fluid that fills the eye drains out.

In some primary open-angle glaucoma patients, the structure of the trabecular meshwork is damaged by fibrosis. Fibrosis is a thickening or scarring of tissue which is caused by an excess amount of matrix molecules such as collagen. Fibrosis of the trabecular meshwork prevents the fluid in the eye from draining out normally, which leads to increased pressure in the eye and damage to the optic nerve.

Dr. Parapuram’s team found that the inactivation of the protein PTEN can cause too many matrix molecules to be deposited in the trabecular meshwork, leading to fibrosis. On the other hand, when PTEN activity was increased, it reduced the amount of matrix molecules being deposited in the trabecular meshwork. These results indicate that drugs that can activate PTEN have high potential to be used as a treatment for open-angle glaucoma.

“There’s an immediate need for a new generation of therapeutic drugs for more effective treatment of glaucoma,” says Dr. Parapuram, a Lawson scientist at St. Joseph’s Health Care London and an assistant professor in the Departments of Ophthalmology and Pathology at the Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry, Western University. “While further research is needed, drugs that activate PTEN could be the answer.”

Dr. Parapuram’s team will continue to study the function of PTEN in the trabecular meshwork in more detail and test the role of drugs that activate the protein as a potential treatment for primary open angle glaucoma.

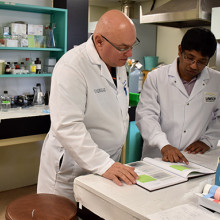

Dr. Michael Motolko (left), Chair/Chief, Department of Ophthalmology, and Dr. Sunil Parapuram (right).

“This study highlights the expansion of our department’s research activities into basic science application and its findings are relevant to many other fibrotic diseases,” says Dr. Michael Motolko, Chair/Chief, Department of Ophthalmology, Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry,Western University, London Health Sciences Centre and St. Joseph’s Health Care London.

The study, “TGF-β induces phosphorylation of phosphatase and tensin homolog: implications for fibrosis of the trabecular meshwork tissue in glaucoma,” is published in Nature’s Scientific Reports.

Dr. Mark Chandy

MD PhD FRCPC

Stem cell biology, induced pluripotent stem cells, cardiovascular disease.

My research employs molecular biology to understand the pathophysiology of cardiovascular disease. Early in my career, I studied the mechanisms of chromatin dynamics, which have broad implications in the influence of the environment in conditions such as diabetes and smoking. I later helped characterize how transcription factors and microRNA direct cardiovascular differentiation and how perturbations of these mechanisms are implicated in cardiovascular disease. My interest in stem cell biology attracted me to Joseph Wu, MD, Ph.D. at Stanford, to learn more about human induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) disease modeling endothelial dysfunction.

Advances in next-generation sequencing, bioinformatics, and gene editing make it possible to decipher SNPs contributing to cardiovascular disease and disease-specific transcriptome profiles. More precise diagnostic biomarker-based tests could be developed with a deeper appreciation of an individual’s molecular signature. Additionally, personalized medicine could emerge from iPSC disease and advance precision medicine.

As a recently appointed Assistant Professor at the University of Western Ontario, I am now an independent physician-scientist conducting research using iPSC disease modeling that I developed at Stanford University. My research focuses on cardiovascular disease modeling to 1) investigate the effects of the environment on the vasculature, 2) discover biomarkers to risk stratify cardiovascular disease, and 3) discover druggable target genes for cardiovascular disease. The overarching goal of my research is to use iPSCs to understand mechanisms underlying the relationship between inherited factors and how environmental stress, such as diabetes, e-cigarettes, and marijuana, sensitize an individual to exacerbated cardiovascular disease. The discovery of these gene and environment interactions will facilitate the identification of high-risk individuals who could benefit from therapy that alters disease trajectory. In the future, iPSC disease modeling could guide the discovery of sm! all molec ule agonists or inhibitors that could be used as personalized medical therapy for cardiovascular disease.

Aleksandra Leligdowicz

Drug combats underlying causes of Alzheimer-related dementia

A “game-changing” new drug offers both hope and time to some people diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, says the head of a St. Joseph’s program that played a key role in the medication’s clinical trials. Health Canada has newly approved lecanemab (brand name Leqembi, developed by Eisai Co. and Biogen), which has been shown to slow progression of Alzheimer’s disease in people with mild symptoms.

St. Joseph’s Health Care London, and its innovation arm at Lawson Research Institute, has played a key role as one of multiple sites that have trialed the drug.

“This is game-changing,” says Dr. Michael Borrie, medical director of the Aging Brain and Memory Clinic at St. Joseph’s, whose work in dementia research and clinical practice spans more than three decades.

“We’ve been working for over 20 years to find a compound that is disease-modifying. This is the first approved drug in Canada that addresses the underlying pathology of Alzheimer’s, not just the symptoms.”

Lecanemab works by removing amyloid proteins that accumulate as sticky clumps in the brain and are associated with cognitive decline in people with Alzheimer’s. “It reverses one aspect of the disease by removing the plaque from the brain ,” Borrie explains.

“You can characterize its benefit in terms of time saved. If you were to have this medication for four years, you can ‘save’ one year of cognitive decline. It totally changes the course of their neurodegeneration in a way we haven’t seen before.”

Lecanemab was one of many clinical drug trials assigned to research coordinator Kayla Vander Ploeg when she arrived to work at St. Joseph’s more than a decade ago. “For so long, we had hope that one of these medications would benefit patients long-term. Now we have more than hope. We have results,” Vander Ploeg says.

“Today I’m seeing people who say, ‘my dad or my mom was in this study, and now there’s hope for me.’ ”

There are specific eligibility criteria, including confirmed diagnosis – through cognitive testing and through advanced brain imaging and biomarker tests – plus screening to rule out two gene variations that couldresult in more side effects.

Canada is now one of 51 countries to have approved lecanemab.

Borrie cautioned that Health Canada approval doesn’t necessarily translate to funding coverage. It’s not yet determined who will pay for the medication, or how: when lecanemab was approved in the United States in 2023, the annual cost per patient was more than $26,000.

The length of time from drug development to trials to approval illustrates how painstaking pharmaceutical research can be. But it also highlights how integrating health research into hospital settings can translate more quickly into improved patient care.